Battery-powered electric buses are growing in use among transit agencies, but intercity bus operators have been slower to adopt the new technology. That’s beginning to change, industry leaders say.

FlixBus, its partner MTRWestern and James River Transportation have recently tested fully electric motor coaches in intercity service. “We've kind of crossed a threshold,” said Thom Peebles, vice president of marketing for ABC Companies, the North American distributor for motor coaches from Belgian bus maker Van Hool.

Peebles explained that while some operations demand buses that can travel hundreds or thousands of miles, there are many routes in the U.S. that are within the 250-mile range of existing electric vehicles. Two Van Hool electric buses are touring the U.S. and Canada right now: a 75-passenger double-deck motor coach and a 52-passenger single-level vehicle, Peebles said.

Jefferson Lines, which operates daily bus service to 14 states, hosted a demonstration of electric motorcoaches at its Minneapolis facility last month, including the 52-passenger Van Hool vehicle.

Kevin Pursey, director of sales and charters at Jefferson Lines, said that the 250-mile range of the electric bus fits several routes the company has. “From our perspective, it really would be important for us to get a head start on this,” Pursey said.

For a few days in July, FlixBus and MTRWestern put the Van Hool double-decker coach into revenue service between Seattle and Vancouver, Canada. “People love it. Drivers love it,” said FlixBus Inc. President and Chief Operating Officer Pierre Gourdain. He said the electric coach was quieter and rode more smoothly than comparable diesel-powered buses.

But an electric bus can cost twice as much as a diesel vehicle, Gourdain said. The economics, he explained, preclude running just one electric bus. “For me, the right numbers are probably between three and five [buses] and that means a $5 million investment plus another half-million for the chargers,” he explained.

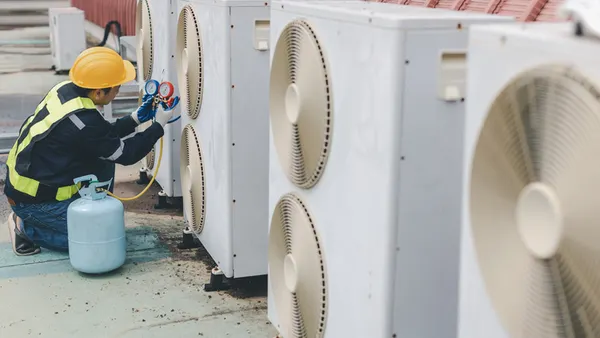

Unlike transit buses, which can be charged overnight at the bus depot, intercity buses may need to be recharged on the road. Pulling into a public charging station, where a bus could easily block four parking spots, isn’t practical, Gourdain added.

Peebles said that’s one of the key challenges, not only for intercity bus lines but long-distance truckers as well. “We're gonna have to get a seat at the table on a lot of the infrastructure spending that's happening,” he said.

Nevertheless, there are use cases for private-sector bus operators to begin trying battery-electric buses. Peebles pointed to charter bus companies that serve universities and other institutions that prioritize sustainability.

Pursey said there may be opportunities for states to help with upfront or ongoing costs. Jefferson Lines operates some routes that are partially state-funded. Pursey wants to introduce electric buses: “If the opportunity presented itself as early as 2023, it would be something that we would look at.”

Gourdain believes that customers will pay a premium for the better onboard experience of riding a clean, quiet battery-powered bus. “We are very hopeful that we will have an electric bus on the road either this year or very early next year,” he said.

“The EV bus would give a much-needed image boost,” said Joseph Schwieterman, director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University. “The industry could use that.”