Jessica Lovering is the co-founder and executive director of the Good Energy Collective. Judi Greenwald is the executive director of the Nuclear Innovation Alliance.

After progressives blocked West Virginia Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin’s permitting reform bill in the fall, pundits were quick to scold activists for shooting themselves in the foot over clean energy. The argument from think tanks and universities alike was that the immense greenhouse gas reductions made possible by the Inflation Reduction Act could not be realized without permitting reform, and this was the last chance to pass such legislation before Republicans took control of the House. Many proponents of permitting reform created a narrative that there is an implicit trade-off between building fast and building justly.

We believe this is a false dichotomy. We agree permitting and siting reform is needed, but that its goal should be to undertake environmental reviews and public engagement more effectively and efficiently. When you look at the evidence, the causes of permitting delays are complex, involving a lack of agency capacity, a lack of expertise on niche issues, a lack of a sense of urgency to meet deadlines, a lack of a clearly defined decision point, and poor inter-agency coordination. Even where lawsuits did hold up projects — which was very rare — they were often for legitimate concerns, and could have been avoided through more inclusive and efficient processes. Interestingly, the permitting reform discussion focused on renewable energy and transmission lines but ignored nuclear energy, which has some of the longest permitting timelines in the power sector.

Both of our organizations — Good Energy Collective and Nuclear Innovation Alliance — are working to make licensing of advanced nuclear energy projects more efficient and accelerate deployment with just and equitable siting processes. The history of nuclear energy development offers plenty of examples of how to do siting wrong. Still, the modern nuclear energy industry is doing a lot right and offers valuable lessons for other technologies in the broader transition to clean energy.

To be clear, many of the constraints on the expansion of renewable energy are caused by power grid congestion and the sometimes long distances between renewable energy resources and electricity customers. The solution is to build a lot more transmission lines a lot faster. These constraints are exacerbated by inefficient transmission siting processes, and there are common-sense policy solutions in the Streamlining Interstate Transmission of Electricity Act that could address these. Beyond transmission constraints, however, renewables are facing

growing opposition to siting at the local level in ways that the current approach to permitting reform may be unable to address. Studies have found that 15% to 35% of wind projects face local opposition, and Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law found over 100 local laws prohibiting or restricting renewable energy projects.

Whether it’s a large nuclear power plant or a small solar farm, several factors affect public perception of energy projects. One of the most important is whether the project development process is considered fair by affected parties. Fortunately, siting and permitting processes can be shaped by public policy, and best practices can be shared across the private sector. For the latter, the nuclear industry has many lessons to share, both good and bad.

For the earliest nuclear power plants built in the U.S., utilities chose locations primarily based on proximity to electricity demand and where they could get cheap land, with little to no engagement with neighboring communities. After the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, there was hope that the required environmental reviews would open up the process to public participation. Instead, utilities and project developers reinforced a model that has come to be known as “decide-announce-defend,” investing resources in lawyers to fight lawsuits.

Similarly, the top-down selection process for a nuclear waste repository in the U.S. — which resulted in Yucca Mountain — created strong opposition over time that ultimately led to the project being defunded in 2010. In stark contrast, Sweden and Finland have licensed geological repositories for commercial nuclear waste, and the process was radically different. After a few failed attempts to site a commercial nuclear waste repository, in 1994 the Swedish nuclear power industry refocused its process around volunteerism and open dialogue. They focused on communities already hosting nuclear facilities, compensated them for participating in feasibility studies and environmental reviews, and included social and economic metrics in their evaluations. Most importantly, communities always had veto power to back out of the project at any point.

Finland had a similar process. Most notably, municipalities were put in charge (and funded) to complete the government-required environmental impact assessment. The licensing process had several stages where host communities could opt out. One might assume that Scandinavian countries can get such complex projects built because of a strong central government, but in both cases, nuclear waste is managed by private companies.

The advanced reactor industry in the U.S. seems to be learning some of these lessons already, with many companies planning their first commercial demonstrations in the next few years. For the first build of NuScale Power’s small modular reactor, the company partnered with the Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS), which isn’t a single utility but a collection of 48 municipal and cooperative utilities across six states. Most notably, all member utilities had to decide if they wanted to opt in to the project and how much power they would commit to purchase. While this seems like a very challenging pathway to the first demonstration, it meant

that NuScale had to do genuine community engagement to build trust and address concerns. UAMPS members also had built-in off-ramps from the project before a final go/no-go decision — and some did leave — but ultimately, 27 communities are still committed even after the project's cost increased.

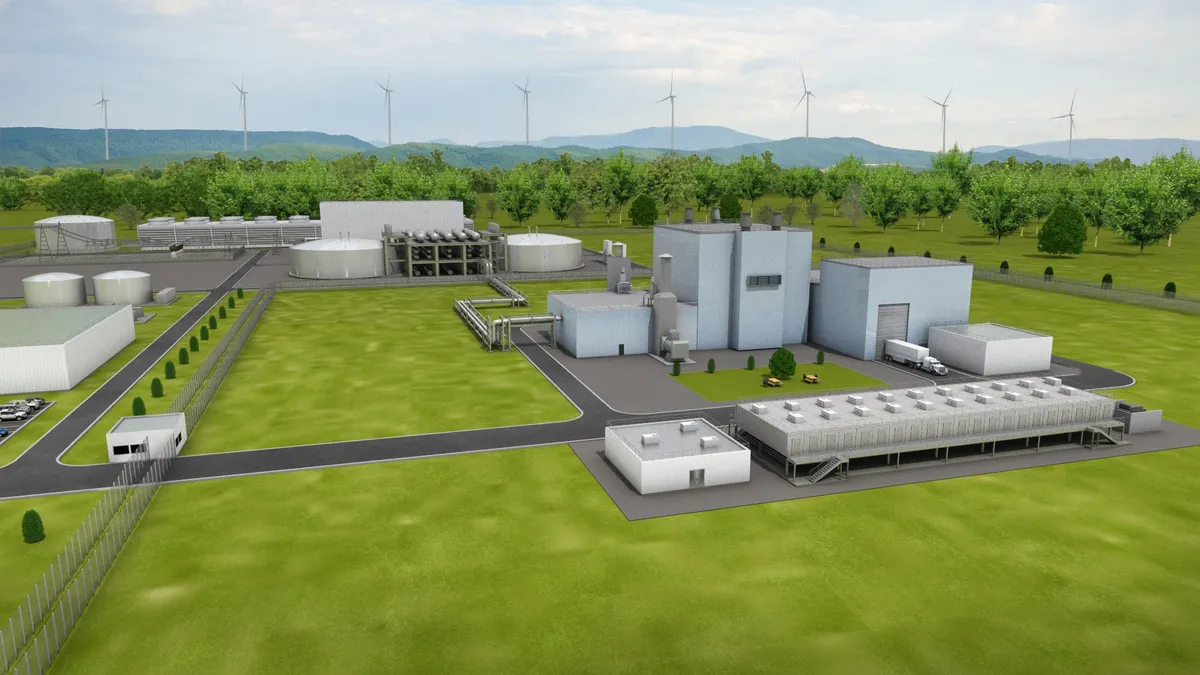

The company Terrapower is looking to build its first-of-a-kind sodium-cooled fast reactor in Kemmerer, Wyoming, but a lot of work went into the selection of the site. Terrapower initially announced it was interested in Wyoming — a state with no nuclear power but a long history of uranium mining — and worked with four potential communities to fund feasibility studies. Notably, the communities didn’t have to put up any of their own money, and most had coal plants that had retired or were retiring soon. The Wyoming state government has been very

supportive, passing legislation to aid in licensing reactors and offering tax exemptions, but also commissioning studies on waste, siting and job impacts that could help communities decide if the projects offer enough benefits.

We believe that a fair and just siting and permitting process for energy infrastructure will result in more successful projects that can still be built fast. But designing good processes will depend on whether we’ve learned from past mistakes. A good siting process looks for places favorable toward a project, offers funding and trusted experts to help communities understand the impacts and risks and gives communities off-ramps to quit a project at various points before a go/no-go decision is made. For permitting there needs to be clarity at the start on who has jurisdiction and transparency in how decisions are made. Affected communities need to be well-informed of the

risks and provided a forum to ensure their concerns are not just heard but addressed.

And these processes must be timely, with a clearly defined decision point, because timeliness, justice and climate protection go hand in hand. Interminable processes are inherently unfair because they require time and resources that ordinary people don’t have. In the past, the implicit assumption was that it was OK for it to take years or even decades to build energy projects because the status quo was acceptable. We know now — and perhaps we always should have known — that the status quo is not, in fact, acceptable. The need to build out clean

energy infrastructure is urgent. And justice delayed is justice denied.