Ruhani Arya is the vice president of infrastructure and sustainable finance at Bank of America.

The world’s biggest energy challenge isn’t technological — it’s financial.

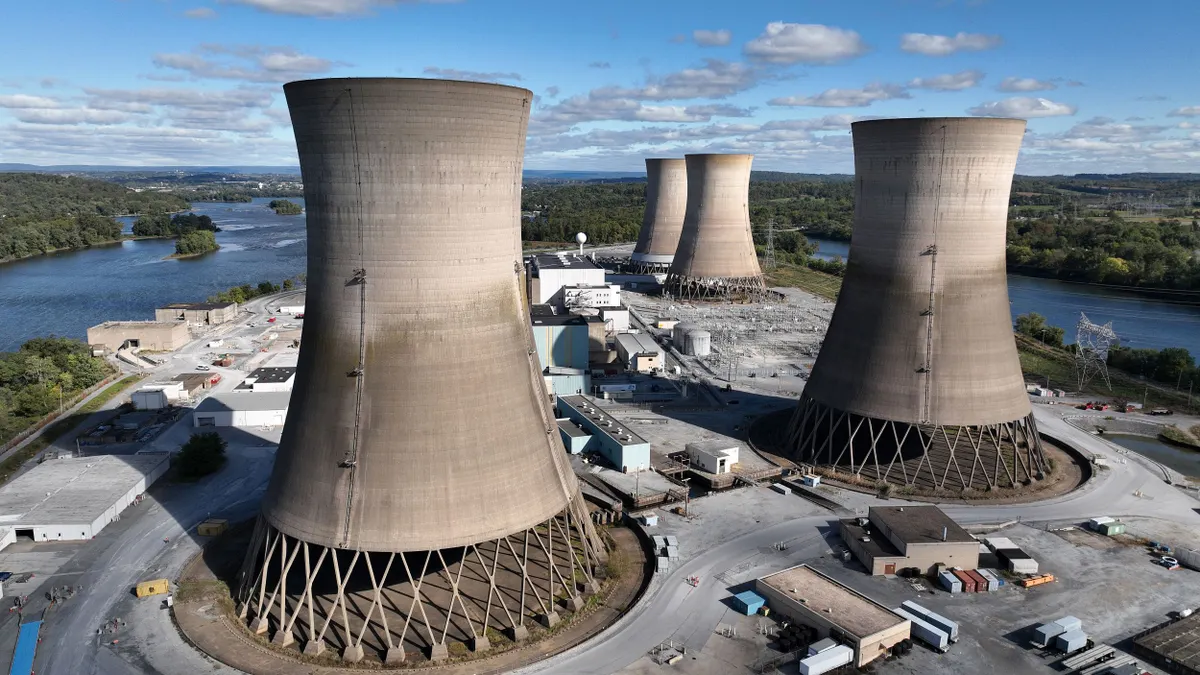

America knows how to build nuclear power plants. More than 400 commercial reactors operate globally, including proven Generation III+ designs like the AP1000. Yet not a single large-scale plant is under construction in the United States today.

The barrier is not safety, nor capability, but structure. Decades of on‑balance‑sheet nuclear investments delivered financial pain, regulatory paralysis and public skepticism. The next wave of nuclear must be financed differently — through project finance, not corporate balance sheets — if it is to scale fast enough to meet demand from data centers and other industries.

The coming demand shock

Under current policies, annual U.S. industrial electricity demand is forecasted to grow 13% from 2025 through 2050, according to an analysis by the Rocky Mountain Institute. Under a high emissions reduction scenario, total annual electricity demand is forecasted to grow 139% over the same period, it said.

AI and hyperscale data centers are already reshaping load growth curves. By 2030, those facilities could consume up to 12 percent of U.S. electricity, according to McKinsey.

Their demand is continuous and thus impossible to meet with wind and solar energy alone; they need baseload power. Enter nuclear: carbon‑free, 24/7 and grid‑stabilizing. But without a viable way to finance new reactors, this resurgence will stall before it starts.

What project finance solves

Traditional corporate financing concentrates exposure. If a nuclear plant’s cost doubles — as it did for Georgia Power’s Vogtle Units 3 and 4, rising from about $14 billion to more than $30 billion — shareholders and ratepayers, not the asset, take the hit, sometimes triggering credit downgrades and inflating utility debt borrowing costs.

Project finance addresses this issue. Each facility sits in a dedicated special‑purpose vehicle (SPV), separating debt and liabilities from the parent’s balance sheet. Investors fund an asset, not a utility. Lenders rely on contractual cash flows, not corporate guarantees. Project finance involves a risk allocation structure that disciplines cost estimation and aligns incentives among builders, operators and financiers.

This model fuels nearly every major energy infrastructure investment outside nuclear — from LNG export terminals to solar and wind projects. There is no reason nuclear should remain the exception.

Structuring nuclear project finance

A realistic approach would mirror today’s large‑scale data center development with a hybrid of project, infrastructure and real‑estate finance:

- Reactor designer, developer and engineering, procurement and construction companies: Provide standardized designs and fixed‑price, turnkey construction.

- Equity partners: Infrastructure funds, pension investors and sovereign capital contribute equity through construction, earning higher returns for assuming early‑stage risk. Private markets currently sit on $350 billion in dry powder — an enormous potential pool for nuclear. Upon commercial operation, utilities or long‑term asset owners/operators can potentially acquire the stabilized asset.

- Debt providers: Banks and insurers lend long‑tenor debt, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, which can guarantee up to 80% of eligible cost. Insurance capital, particularly from life insurers seeking duration‑matched assets, can provide supplemental debt tranches.

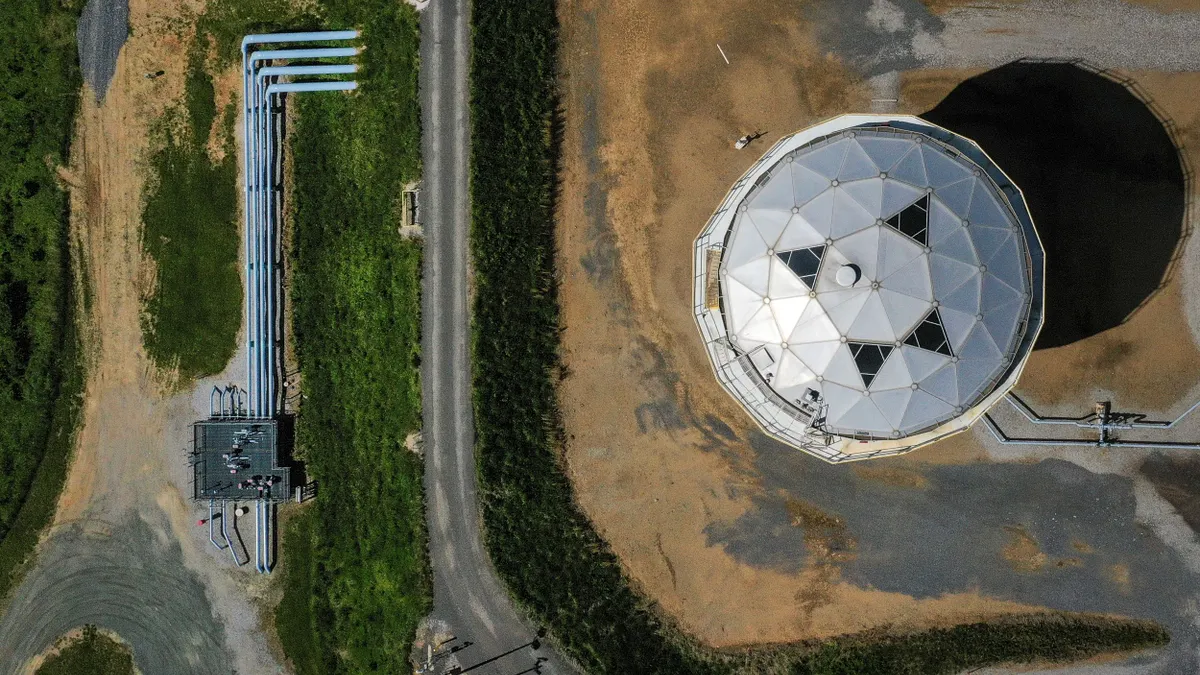

- Offtakers: Tech or industrial companies sign long-term power purchase agreements for baseload nuclear power. As AI and cloud demand surge, three to five major offtakers could easily underwrite several reactors’ output, providing predictable revenue streams and unlocking cheaper financing.

- Government incentives: The 30–40% tech-neutral investment tax credit established via the Inflation Reduction Act applies to the fair market value, not the initial cost estimate. This structure effectively provides a cushion against budget overruns, a feature that could boost confidence of nuclear investors to move forward with new projects.

This blend of stakeholders produces bankable capital structures and, crucially, decouples nuclear investment from utility risk.

Lessons from Vogtle

Vogtle’s difficulties stemmed from timing, rather than technology.

At financial close, the AP1000 design was incomplete, the U.S. supply chain immature and the workforce untrained. By 2017, after management reorganization, costs stabilized near ~$26 billion, roughly aligning with post‑COVID final numbers. If anything, Vogtle’s final price tag of $32–$36 billion confirms the need for project-level scrutiny, rather than discrediting the technology.

The upside: Vogtle created a trained workforce of 30,000 people and validated a now‑mature supply chain. The next series of reactors could capture at least 20% cost reduction and 30% higher efficiency through standardization — the same learning curve that was observed from Vogtle Unit 3 to 4.

Reforming regulation and capital costs

Cost escalation in nuclear has often stemmed from regulation. The ALARA (“as low as reasonably achievable”) principle, though well intentioned, has enforced excessive conservatism.

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has a single mandate: safety. By contrast, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration balances safety with societal benefit. A similar dual mandate for the NRC could align nuclear policy with national economic and environmental goals, reducing investor risk premiums and project discount rates. Overregulation that ignores these realities deters capital, slowing progress toward environmental and industrial security.

A stable regulatory environment lowers project discount rates, directly improving competitiveness. Every 100‑basis‑point reduction in cost of capital cuts the levelized cost of electricity by roughly five to six dollars per megawatt‑hour. With available tax credits, government loans and standardized project financing, nuclear LCOE could approach $60–$70 per MWh, putting it well within commercial viability.

Why it matters now

America’s grid faces booming demand. Nuclear energy can be part of the answer — and project finance is the key to building more reactors. It allows capital markets, not utilities, to shoulder construction risk and aligns modern investors’ appetite for long‑duration, asset‑backed returns with national industrial and environmental goals.

Nuclear’s problem has never been physics or public interest; it’s been finance. But with fleet standardization, federal incentives and a project finance structure that puts accountability where it belongs, that barrier can finally fall. This isn’t nuclear’s last chance. It’s the first credible one in decades.