Carbon pricing took center stage at the second and final day of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s technical conference on wholesale power markets on Tuesday, as stakeholders searched for ways to integrate state policies into the organized market construct.

FERC called for the conference in March over concerns that state power incentives — particularly nuclear subsidies and renewable portfolio standards — could unravel the organized market construct.

In the first day, FERC heard testimony from state regulators and organized market operators. Anxiety over the state policies for renewables and decarbonization was a common theme, but stakeholders were largely unable to agree on any concrete plans for reforms.

That was the case on the second day of the conference as well, as FERC heard from generation owners, academics and consultants. As FERC Chair Cheryl LaFleur promised last month, there was no “white smoke” billowing out of the commission’s hallways at the end of the conference on Tuesday — many stakeholders remain divided on current incentives and a comprehensive solution proved elusive.

But short of a complete answer to market issues, one noteworthy area of consensus emerged from nearly every corner of the diverse stakeholder group — the need to price carbon in wholesale power markets.

“The states have a lot of objectives. There is one that stands out as most transformative … that is decarbonization,” said Sam Newell, a principal at the consulting firm Brattle Group. “Some states are aiming for 80% decarbonization within one investment cycle from where we are today. To me, that is the one to focus on most, and it’s also the one that I think is most readily integrated into wholesale markets.”

Integrating decarbonization goals into markets will likely mean devising mechanisms to price carbon and incorporate other clean energy goals into wholesale markets, stakeholders said. Working out how exactly to do that is set to be a focus for FERC in the wake of the conference — as long as new appointees do not change its course.

Sparks fly over nuclear subsidies

The second day of the FERC technical conference was heated by sector standards, as a panel of state regulators and generators debated nuclear subsidies in New York and Illinois.

Last August, New York regulators unanimously approved zero-emission credits (ZECs) for three upstate nuclear plants, awarding them $7 billion over 12 years to keep them from retiring. Soon after, the idea spread to Illinois, where the legislature passed a ZEC program to support nuclear plants. Now, conversations for similar initiatives are underway in Ohio, Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Independent generators despise the subsidies, which they fear will crater prices in the capacity market, preventing their unsubsidized plants from earning sufficient returns and ultimately disincentivizing new builds. They are challenging both the New York and Illinois subsidies in court and at FERC.

The morning session pitted a group of these generators — including NRG, Calpine and Invenergy — against Exelon, whose plants are the beneficiaries of the subsidies in both states.

The generators pulled no punches, ganging up on Exelon for what they see as bailouts for otherwise uneconomic generation.

Invenergy CEO Michael Polsky compared the ZECs to the dumping of subsidized Chinese goods on other countries. The ZECs, he said, are “completely subsidized power in kWh, basically [saying] to Exelon: ‘You sell the electricity for whatever price. Even if you lose money, we’ll pay the difference.’”

“Talk about China dumping...” he said. “What more dumping can we talk about than this?”

Polsky drew a comparison between renewable energy credits (RECs) awarded for the building of wind and solar facilities and the ZECs given to nuclear plants. At least in the former case, companies have to compete to build the resources that get RECs, he said, but certain nuclear plans are simply awarded ZECs.

“We rely all the time on market-based policy, even if it’s subsidized policy, but it’s market-based,” he said. “People have to compete to get something. [It’s] not just given to them on a silver plate.”

On the first day of the conference, Bob Flexon, the CEO of Dynegy, another generator, warned that competitive generation in the MISO market would “vanish” as a result of the Illinois ZECs suppressing market prices and making other plants uneconomic. A key worry of generators and market operators is that the subsidies will disincentivize investment in new plants as well, potentially creating reliability problems down the road.

According to Calpine CEO Thad Hill, that’s already happening.

“In our sector, capital markets are not allowing any of the public companies to invest $1 in these markets because of where we are,” he said.

Exelon’s head of federal policy Kathleen Barron gave a full-throated defense of the ZEC policies, saying that “by any measure,” keeping her company’s nuclear plants online was the cheapest option for states looking to decarbonize.

“The state stepped in because it was cheaper to do that than to bring on new clean generation,” Barron said. “They didn’t stop. They are going to pursue new clean generation through RPS programs and other mechanisms [as well].”

The carbon consensus

Hours of debate found little common ground on ZECs, but there was much more consensus on what should come next. On the first day of the conference, New York ISO CEO Brad Jones said his intention was to use the ZECs as a “bridge to the future,” eventually replacing them with carbon prices in the wholesale market.

Exelon has long supported carbon pricing, even arguing for it as an implementation strategy for the Clean Power Plan. But the independent generators at the conference also endorsed the concept.

"We need to ask markets to do the right thing,” said Abraham Silverman, counsel at NRG Energy. “There’s nothing magical about the existing structure. It’s an accident of history.”

Silverman stressed that only FERC can ensure just and reasonable rates in the face of state carbon goals. One option would be to move to “security-constrained economic carbon dispatch,” with a capacity market that features competitive tranches for various resources, he said. Invenergy's Polsky, meanwhile, stressed that any award of new state subsidies should be on a competitive basis.

While the generators largely gave support for a carbon pricing proposal, the consensus stopped at Maine PUC Chairman Mark Vannoy. He said his state would support pricing other attributes (such as reliability) in the wholesale market, but not carbon, as it is too expensive.

Vannoy was challenged by Pennsylvania PUC Vice Chair Andrew Place, who pointed out that revenues from a carbon price can be returned to states and ratepayers, so “it’s not a net loss.”

But while popular, carbon pricing is unlikely to be a panacea, Silverman warned. With RPS policies and subsidies, states aim for new jobs and technological development in addition to carbon reductions, so a carbon price may not serve all their needs.

“We don’t necessarily think putting a price on carbon directly … is actually the best way to incent renewables,” he said. “We think long-term [bilateral contracts] have been successful getting new renewables built — something we do all day and night.”

Consultants, academics voice support

That same qualified support for carbon pricing was apparent during FERC’s subsequent panel of power sector academics, analysts and consultants. While the group of industry veterans held diverse opinions on the correct structure of wholesale markets, all agreed that FERC and the states should find a way to integrate important attributes like carbon intensity into market prices.

“Having done the analysis, I can tell you that if New York were to move forward with a price on CO2 emissions and no subsidies, we wouldn’t be talking about the need to pay nuclear units to keep running,” said Lawrence Makovich, chief power strategist at consultancy IHS Markit. “The market prices would keep them running.”

Bill Hogan of the Harvard Electricity Policy Group said the social cost of carbon — an estimate of greenhouse gas pollution harms — should be the benchmark for whether FERC attempts to accommodate state policies into the wholesale markets. Because the Trump administration dissolved the interagency working group tasked with calculating that cost, Hogan said the responsibility now falls to FERC.

“You should be very encouraging of things that follow the social cost of carbon you’re now responsible for estimating,” he said.

But like NRG’s Silverman, some analysts stressed that carbon pricing would likely not replace all of the around-market actions states are currently taking.

“I think it’s really clear that states want to promote carbon-free, but they also want to promote innovation and technology,” said Cliff Hamal, a managing director at Navigant. “No one’s building offshore wind because they think that’s the cheapest … arguably, they are doing us a favor by developing a new technology which shows great promise down the road.”

There are certain market constructions that could allow the integration of these goals, said Robert Stoddard, a consultant speaking on behalf of the Conservation Law Foundation. He proposed a forward clean energy product — the Carbon-Linked Incentive for Policy Resources (CLIPR) — that could ostensibly replace RPS standards and cut down on negative energy market pricing seen in California and Texas recently.

“The key property is that it’s much like a REC, but that the value in any hour is not fixed and flat, but depends on the marginal carbon intensity in the hour,” Stoddard said. “So when the marginal capacity market carbon is zero, it’s worthless. If you’re running your windmill, but not offsetting carbon, you’re not getting paid.”

Likewise, he said, storage facilities would have an opportunity to pick up those free incentives during zero marginal carbon hours and then feed the power back into the grid “during the middle of the day when the carbon offset is very high.”

“It creates a carbon-like price, but particularly for units that are able to respond to carbon and helps sort out which units are actually doing the best in terms of offsetting,” he said.

The details of the proposal still need to be worked out, but it attracted attention from FERC Commissioner Honorable, who highlighted it for the record as a potential avenue for state-federal cooperation.

Alone in the swamp

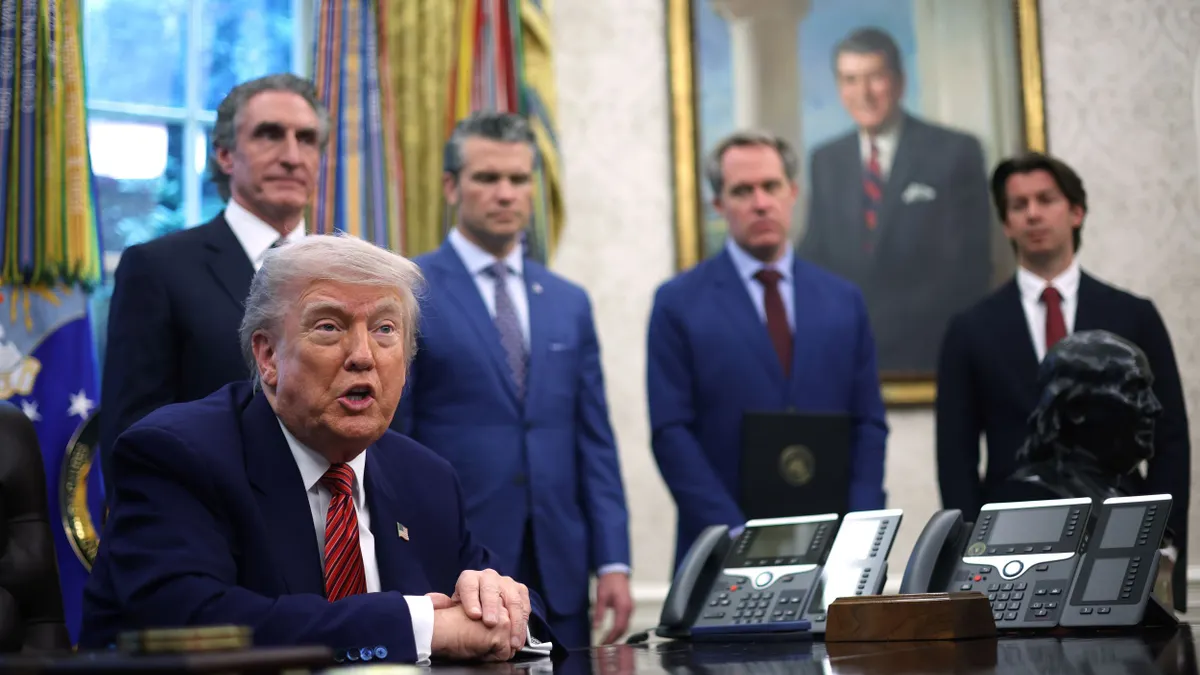

While power sector stakeholders appeared in relative consensus on carbon pricing at FERC, they are outliers in Washington. In addition to suspending the social cost of carbon group, President Trump has moved to roll back a number of Obama-era environmental regulations, a point spotlighted by Sue Tierney of the Analysis Group.

“I bet this is the only federal building in Washington, D.C. where there is a discussion of carbon pricing and deep decarbonization,” she said to laughs from the crowd. “So very good, FERC. We like it.”

But whether those discussions will continue is up in the air. After Commissioner Honorable steps down in June, FERC will be left with just one commissioner, and it needs at least three for quorum.

While the president is said to have settled on three nominees — lawyer Kevin McIntyre, Senate aide Neil Chatterjee and Pennsylvania PUC Chairman Robert Powelson — not one of the figures were present at the conference, nor have they indicated how they would handle state carbon goals.

Ostensibly, the appointment of three Republican commissioners could change FERC’s tack. But as long as states continue to pursue decarbonization, the impacts on the market will continue to be FERC’s problem. That, analysts noted, was the whole point of the technical conference in the first place — states pushing FERC to act, not the other way around.

Until something changes, Honorable said a key focus for state and federal regulators going forward will be working on proposals like CLIPR that attempt to integrate carbon pricing and other attributes into the market. Whether they are successful will help determine the future of competitive power markets in the U.S.

“We really think [carbon pricing] is the key,” Honorable said, summing up the conference proceedings. “Practically, is it achievable?