Anna Littlefield is the carbon capture and storage program manager at the Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines. Simon Lomax is a policy adviser to the Payne Institute. Morgan Bazilian is the Payne Institute’s director and a former lead energy specialist at the World Bank.

Tech giant Google recently announced a landmark deal to capture and store carbon dioxide emissions from a new natural gas plant that will provide electricity to the company’s data centers in Iowa.

It’s a big deal for Google, but quite possibly an even bigger deal for supporters of carbon capture and storage technology, which traps the exhaust emissions from a power plant and injects those emissions deep underground.

For decades, widespread adoption of CCS technology in the U.S. power sector has been an elusive goal — but the fast-growing electricity demands of data centers could be a game-changer.

Data center developers are scrambling to secure power generation options of all types in a global race to dominate the emerging field of artificial intelligence. In just the next few years, AI-driven electricity demand may double and possibly triple to reach 12% of total U.S. power consumption, according to projections from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

To be sure, this challenge is bigger than any single energy source. Google itself has separately announced a partnership with NextEra Energy to bring a mothballed nuclear power plant in Iowa “back to life,” in part to support its data centers there.

Other energy options that data center developers are chasing include advanced geothermal, wind turbines, solar panels, battery storage and demand-side measures to improve the efficiency of data centers, including advanced cooling technologies.

But natural gas turbines will also play a big role, especially in the short term.

Gas-fired power plants are already the No. 1 source of electricity in the U.S. They can provide “firm” power at all hours of the day and night, and they can adjust their output to make room for renewables like wind and solar when weather conditions are favorable.

But for tech companies like Google, the carbon dioxide emissions from natural gas power plants can run afoul of their environmental goals — hence their interest in CCS technology.

To be clear, tech companies aren’t alone in this regard. In the U.S., there are more than 270 publicly announced CCS projects in the energy and industrial sectors, and the recent federal budget reconciliation bill expanded the tax incentives available for the deployment of this technology.

These tax credits have attracted bipartisan support because CCS is viewed as a promising technology that needs assistance during the early stages of deployment, akin to the support wind and solar have received in the past.

Specifically, tax credits can help early-stage natural gas with CCS projects overcome the challenge of “parasitic load,” or the amount of power it takes to run the carbon capture equipment, which reduces the power plant’s overall electrical output.

Site, permitting and legal requirements

How many other data center developers will follow Google’s lead in pairing natural gas power plants with CCS technology?

The answer may depend on where these data centers are built. For natural gas-fired power plants serving data centers to implement CCS, their siting needs to meet several criteria:

First, data centers ideally should be located close to demand centers — such as metropolitan areas — to avoid latency and reduce transmission losses.

Second, energy access must include a reliable natural gas supply with ramping capability, meaning proximity to gas pipelines or gas-producing basins.

Third, there must be water available for cooling and to support the operation of the carbon capture equipment.

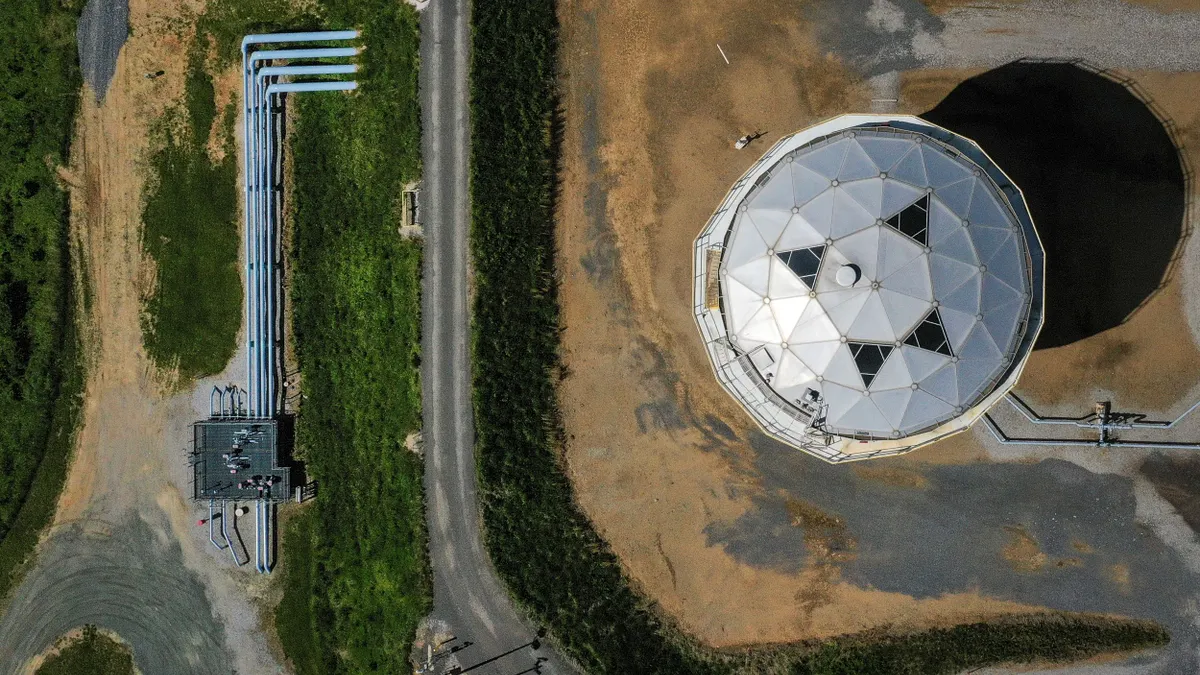

Fourth, access to carbon dioxide storage must be secured, which is no easy feat.

The geology of the area must support permanent storage in deep underground formations. State and federal permitting frameworks for injection wells are required. Legal questions concerning pore-space ownership must be addressed.

Physical infrastructure to transport, inject and monitor the stored carbon dioxide must already exist or have a clear pathway towards permitting and construction.

There are promising signs of this idea gaining traction across the tech sector. Months before Google’s CCS announcement, AI infrastructure provider Crusoe — developer of the 10-GW Stargate project in Texas — announced that another 10 GW data center campus would be built in southeast Wyoming in partnership with energy infrastructure operator Tallgrass Energy.

While the announcement did not specifically call for the immediate use of CCS technology, a major factor in the site selection process was the “existing CO2 sequestration hub” operated by Tallgrass, which will “provide long-term carbon capture solutions."

By choosing locations that meet all these criteria, data center developers can give natural gas with CCS technology the best physical and economic conditions for success.

In turn, America’s AI developers will have access to a firm, scalable power source during a critical growth phase. They’ll also have a power source that aligns with the tech sector’s environmental objectives — and supports continued expansion — while new nuclear, advanced geothermal, low-cost battery storage and other options are still in the works.

Under the right conditions, and in the right locations, natural gas power plants paired with CCS technology may offer a practical bridge between AI’s growth and a lower-carbon power system.