Arjun Krishnaswami is a senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists.

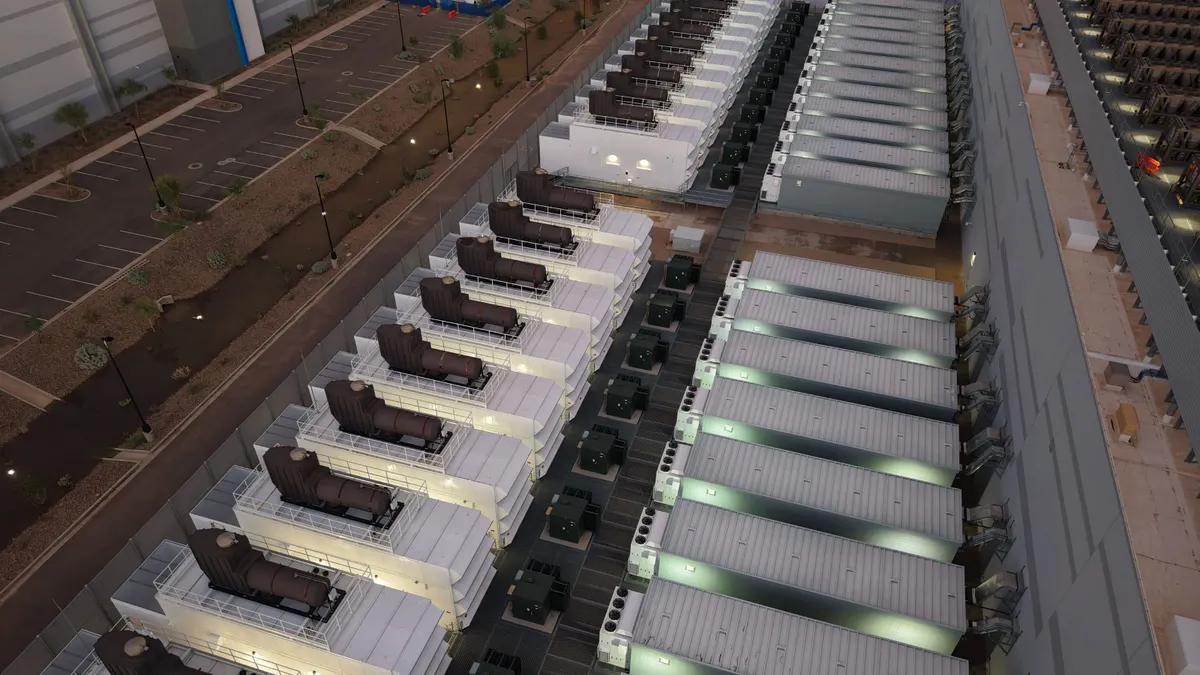

Soaring electricity bills are squeezing pocketbooks and threatening small businesses, making them a main-stage political issue. These concerns are creating momentum for good policies that can stave off price increases — from making it easier to build cheap clean energy projects to requiring data centers to operate flexibly to avoid straining the grid.

We should go full-steam ahead on these near-term fixes, but taking this path alone will be insufficient. These policies target the drivers of imminent rate hikes but don’t address the core reasons that bills are already too high. Unless we change the fundamentals of utility policy, many people will continue to struggle with bills, and prices will continue to rise.

The amount people pay for their electricity rose 13% across the country from 2022 to 2025, with increases in some states exceeding 20%. These hikes are adding fuel to an existing fire: 80 million Americans already struggle to pay their utility bills, and nearly 40% of households sometimes sacrifice basic needs like food or medicine to keep the lights on.

What is driving higher prices? According to a recent study from Lawrence Berkeley National Lab the major culprits are increased spending to replace aging poles and wires, volatile natural gas prices, and growing costs of wildfires and other disasters. The study also found that households have faced worse price hikes than businesses.

These factors share a common thread: they have raised bills as a result of a regulatory system that by default passes costs and risk onto customers, encourages overinvestment in conventional solutions, and hampers innovation. When we accept the traditional utility model as a given, regular people pay the price.

The traditional model allows utilities to use customer bills to recover the costs of generating or purchasing power, building infrastructure, and operating the grid. The approximately 75% of Americans served by for-profit utilities also pay for a guaranteed profit for shareholders on certain capital expenses, including investment in powerlines and substations and, in some states, power plants. Key decisions on what to build and how to set rates for different types of customers are made through utility proposals that are approved by state regulators.

Today, customers must foot the bill for any increase in expenses — exposing regular people to the risk of volatile natural gas prices, cost overruns, or climate impacts. For example, the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia went more than $16 billion over its $14 billion budget. The company building the plant went to the Georgia public utility commission multiple times to ask for rate increases to cover the cost overruns and complete the project, and the commission approved.

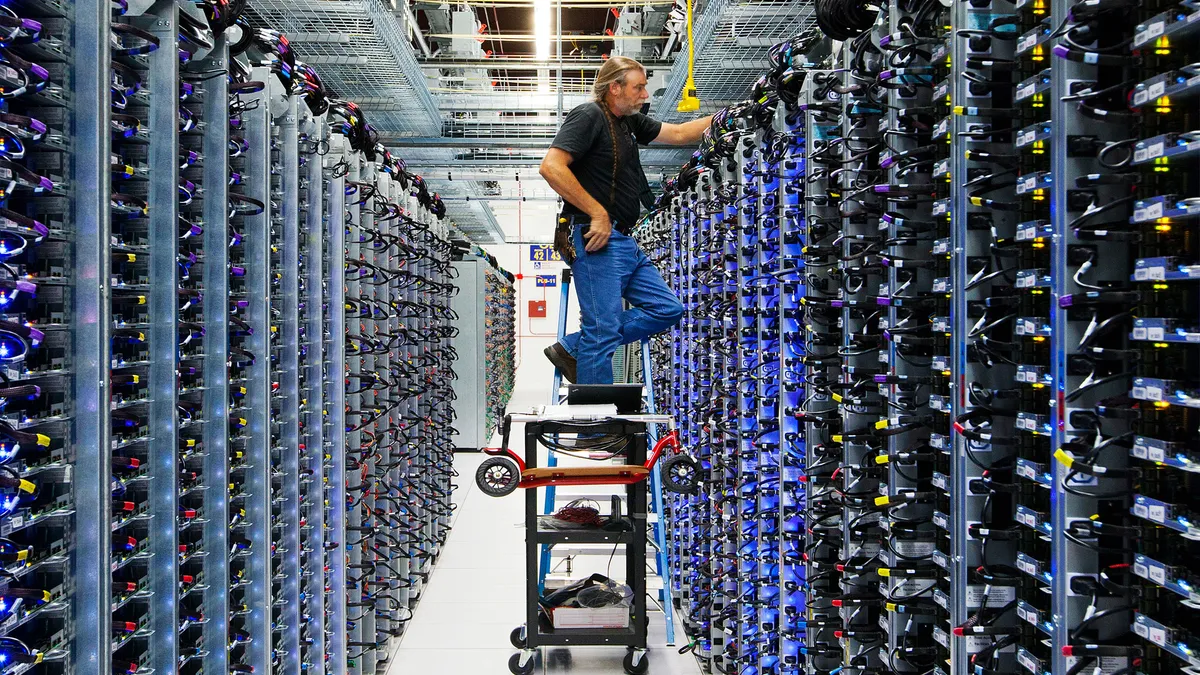

The current model also rewards utility shareholders for higher spending on traditional solutions that earn a profit, which in turn increases bills. For example, when considering an aging grid that is tasked with meeting growing demands, companies make more money by building more power lines and substations than by using customer-owned generation and storage that would reduce utility expenses.

As a result, utilities tend to build more than is needed and avoid solutions that don’t earn them a return. That means bills have slowly risen as utilities propose — and commissions approve — greater and greater investments into the system.

The answer is not less investment — maintaining a reliable grid requires spending, and we will need even greater investment to power new industries, replace polluting fossil fuels in buildings and vehicles with electricity, and guard against worsening climate disasters. Rather, we must break status quo thinking to unlock policy that protects regular people while enabling the major infrastructure investments we do desperately need.

At the center of this issue is a fundamental question: who should pay to maintain a reliable and resilient grid that is responsible for an increasing share of economic growth?

The default answer is customers, but as the need for spending on the grid increases, policymakers should look to new places to cover those costs. For example, using state budgets to cover a portion of utility expenditures could shift the burden away from working class people, who are hit hardest by high bills, onto high-earners and corporations. In addition, historically utilities have used higher household bills to subsidize businesses through lower rates — it is time to flip that script and require some customers, such as massive data centers, to pay more so that families and small businesses can get by.

We should also stop burdening customers with the electric sector’s risk, whether from volatile fuel prices, cost overruns, or climate impacts. Why should regular people always take the hit when things go wrong?

Instead, we could design rates to split fuel price risk between the companies and customers, creating an incentive for utilities to better plan for natural gas volatility. And in the aftermath of wildfires and hurricanes, shareholders and state governments, not customers, should foot the bill for the impacts and cover the costs of preparing for the future. Throughout the western United States, the increased prevalence and severity of wildfires is sparking this very conversation.

High bills should also galvanize a conversation about how to determine utility profits. Redesigning profit motives encourages companies to explore solutions like customer-owned solar and flexible demand that can reduce costs. Some states have already changed their rules to reward utilities for performance, rather than for investment.

Public financing can also reduce costs by removing utility shareholder returns from peoples’ bills. A new law in California unlocks creative public financing for new transmission lines, which will reduce the impact of new investment on household’ bills.

Finally, we must question the default processes for answering these questions. Today’s model relies on checks and balances between regulators and utilities. Too often, regulators have lacked the will or the resources to keep companies in check and have tended to largely defer to utility proposals. Customers have paid the price. We need utility regulators to be main characters in questioning old assumptions and finding new approaches.

These are big questions, and the answers may butt up against powerful interests that benefit from the status quo. But without them, we will not solve our electricity affordability challenges, and if the recent Georgia elections are any indication, people are ready for a new path.