Senators on Wednesday touted their desire to advance permitting reforms, but a key Democrat said progress hinges on the Trump administration ending its moves to halt renewable energy development, including for projects that are fully permitted and being built.

“It makes no sense to pass a bipartisan permitting reform that gets illegally butchered by a lawless executive branch,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

The responsibility for reviving permitting reform efforts in Congress rests with the White House providing “credible confidence that the nonsense will stop,” he said during a hearing on permitting reform.

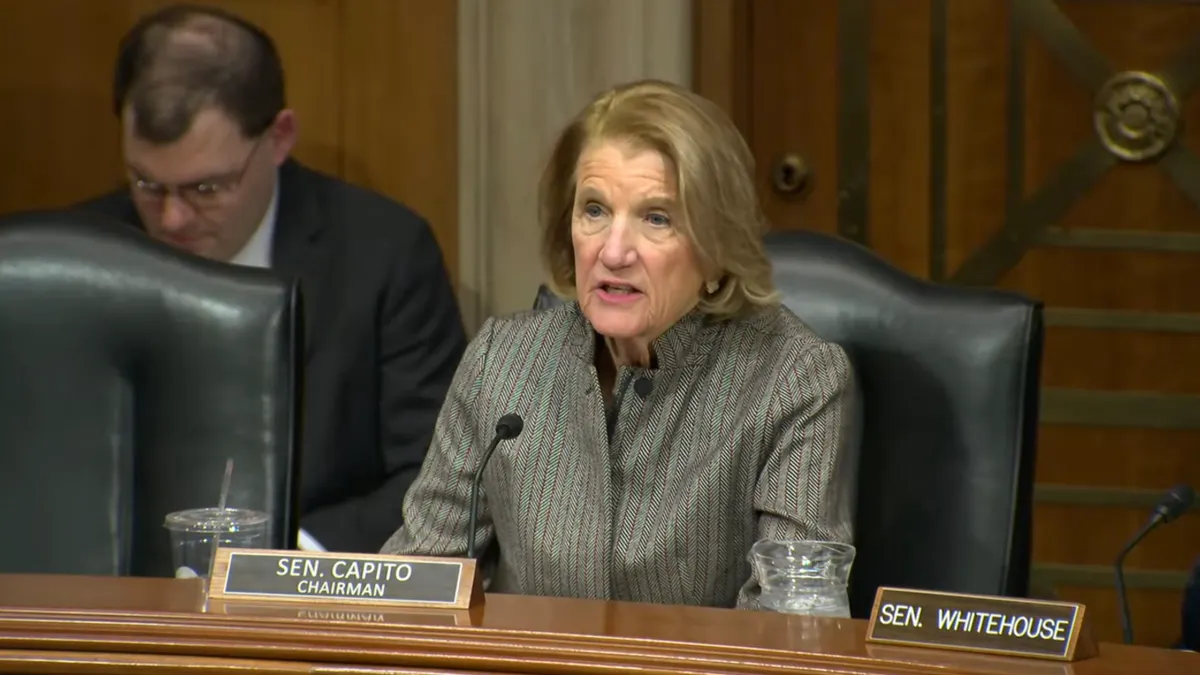

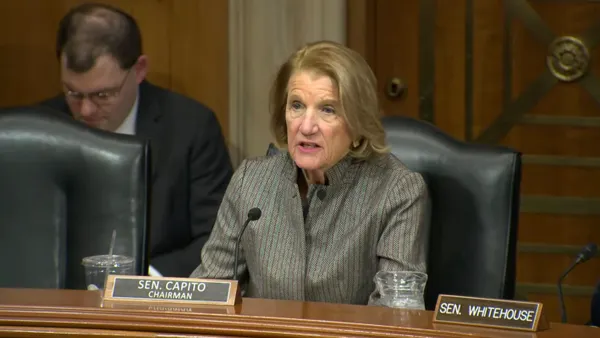

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, R-W.Va., committee chairman, said she called the hearing with Whitehouse “to get us back on the path to fruitful compromise.”

As recently as a month ago it appeared that after years of efforts, permitting reform was advancing in Congress.

The House on Dec. 18 passed the Standardizing Permitting and Expediting Economic Development Act, called the SPEED Act, which revises the National Environmental Policy Act, the law requiring federal agencies to assess how their actions affect the environment.

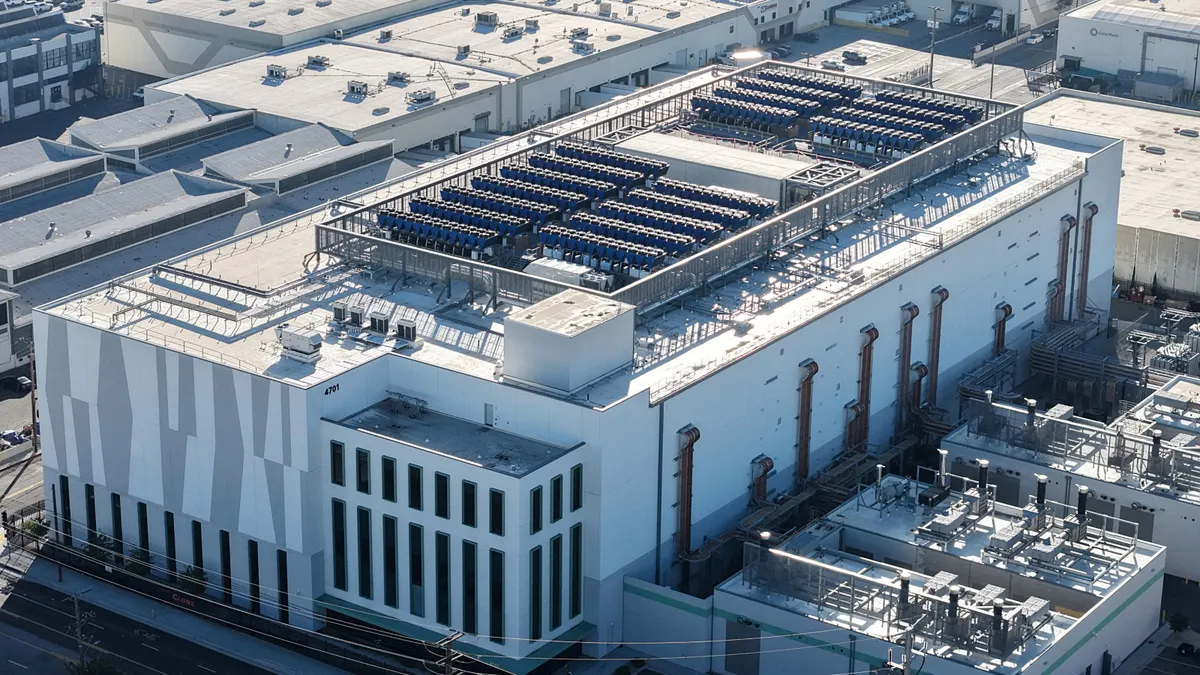

However, Whitehouse and Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., ranking member of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, on Dec. 22 ended permitting reform discussions after the Trump administration ordered work to halt on all offshore wind farms under construction, which total 7 GW. So far, federal judges have issued injunctions that allow work to resume on four of the five projects hit with the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s “stop work” orders.

“This is not Democrat versus Republican,” Whitehouse said. “This is legislative versus executive, an executive that won’t honor its constitutional duty to faithfully execute the law.”

During the hearing, Capito said a permitting reform bill must be bipartisan to be effective. It must also be “project neutral” and give project developers “predictability, consistency and finality” in securing permits.

Whitehouse said permitting reform should require early stakeholder engagement and improvements to the federal interagency review process.

The interagency process “is now a place in the executive branch where incompetence and inertia and indolence go to hide, and where turf battles between agencies left unresolved create a lasting squabble that slows down the whole process,” Whitehouse said.

Project certainty was a key issue for lawmakers and panelists at the hearing.

“We have seen the canceling of funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the halting of Inflation Reduction Act projects, and the use of executive authority to revoke permits from already approved, privately financed infrastructure projects,” said Brent Booker, general president of the Laborers' International Union of North America. “These actions raise a fundamental question for this committee: What good is permitting reform, if any project, no matter how far along, can be shut down at the stroke of a pen?”

A future Democratic administration could use the Trump administration’s tactics to limit fossil fuel development, Sen. Edward Markey, D-Mass., said, citing a “memo” from Evergreen Action based on a July 15 Interior Department initiative that set heightened scrutiny for wind and solar projects.

Republicans on the committee pointed to Biden administration efforts that limited fossil fuel development, including the Keystone XL pipeline and a pause on considering approvals for liquefied natural gas export projects.

“We have seen the Democrat administration under President Biden do the same thing that now you're complaining about,” Sen. Cynthia Lummis, R-Wyo., said. “So what we do need is some certainty.”

Permitting reform needs to be based on three core principles, including project certainty for approved projects, according to Abigail Ross Hopper, president and CEO of the Solar Energy Industries Association.

The other principles are reduced timelines through streamlined, coordinated permit reviews and a faster transmission buildout through stronger planning, permitting authority and grid modernization, she said.

Federal project permitting in the United States takes four to five years, on average, according to Brendan Bechtel, chairman and CEO of construction company Bechtel Corp. and chair of the Business Roundtable Smart Regulation Committee. Permitting for power generation and transmission projects takes five years on average, McKinsey & Co. said in a report cited by Bechtel.

In comparison, permitting for an airport project in Australia that Bechtel built took less than three years and a 700-MW hydro project in Canada took two-and-a-half years, he said.