Mothusi Pahl is principal at Hartwell and Loche. He serves on the advisory council of the Alliance for Innovation and Infrastructure and on the board of directors of the Great Plains Institute.

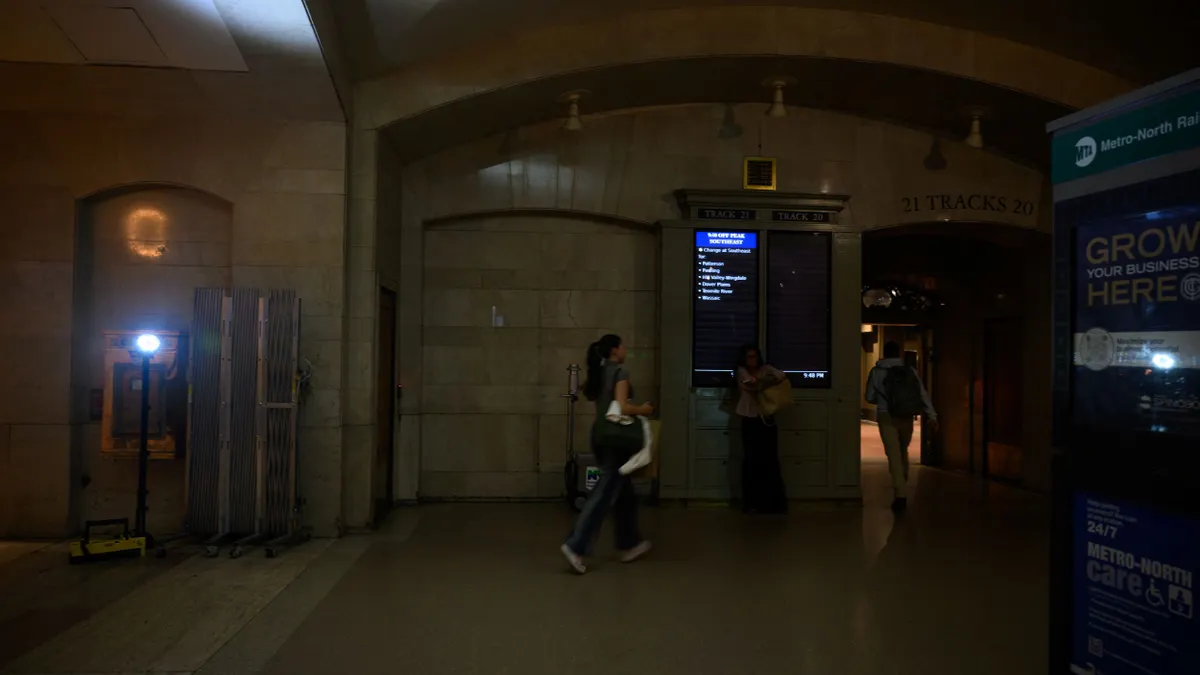

Picture this: You’re a utility executive. It's August 2029. A heat wave grips 10% of the country, and your regional transmission organization is red-lining.

Community concerns around rolling blackouts are pinging on social media. Your operations center makes the call that's become routine over the past three years: You phone Amazon Web Services and ask them to shed 1,000 MW of load. Within minutes, AWS pauses 30% of its data center operations. Crisis averted. Hospitals stay online.

But here's the uncomfortable truth your team doesn't discuss: What happens when AWS decides to say no?

This isn't science fiction. This is a very logical point along the curve of decisions being made right now in utility boardrooms and state regulator offices across America. We're sleepwalking into a future where our electric grid depends on the voluntary cooperation of private technology companies — and we're doing it because the short-term benefits are too attractive to resist.

What I've learned should concern every utility executive and state regulator in the United States: We're building a mutual hostage situation and utilities are negotiating from the weaker position.

How we got here: The seductive economics of flexible load

The math seems simple enough. Data centers are mushrooming across your service territory (even though an increasing number seem to be phantoms), each one consuming the 100 MW to 500 MW equivalence of a small city. Your engineers rightly see this as a grid stability nightmare. But then the data center operators respond positively to your team’s new demand-side management proposal and the result is something irresistible: guaranteed demand response at unprecedented scale.

Unlike residential demand response programs of variable productivity that might shed 100 MW through millions of thermostats, a single data center can curtail firm gigawatts instantly. The Amazon executive explains that some AI model training can pause mid-process. The Microsoft rep notes that cloud workloads are already shifting hour-by-hour on a continental scale. The Google team demonstrates how their systems already optimize around pricing tied to forecasted availability of renewables.

Your procurement team runs the numbers: Instead of building three new natural gas peakers at $1.3 billion each, you can pay data centers $50 million annually to provide the same capacity. It's a financial no-brainer. Your CFO loves it. Your shareholders love it. Your utility commission blesses the big demand response contracts as innovative cost management.

Everyone congratulates themselves on this public-private partnership.

The hidden dependency

Here's what changes over the next three years.

Year One: Data center demand response is a nice-to-have. You use it occasionally during peak summer days. You save ratepayers money. Everyone wins.

Year Two: You defer that third peaker plant. Why build it when you've got reliable demand response? The business case doesn't justify the capital expenditure anymore and your rate payers have made it clear that even indexed cost increases lead to state-level hearings. Your regulator agrees; they prefer demand response contracts to expensive new generation.

Year Three: Your grid operations are now designed around data center flexibility. During your 10-day July heat wave, you lean on data center curtailment for 6 of those days. It works flawlessly. Your grid remains stable. Your CEO highlights it in her annual report.

Year Four: You face a choice between building $3 billion in new transmission infrastructure or signing expanded demand response contracts. You choose DR contracts. The cost of compute is going down, but the political value of grid stability is going up. And who can argue — it's faster, cheaper and more palatable than land use and eminent domain fights for new power lines.

Year Five: August 2029 arrives. Your grid literally cannot function through peak demand without data center participation. They're not helping you anymore. They are essential.

The dependency is complete.

Why utilities have less leverage than they think

Utility executives assume they hold all the cards. They don't.

Data centers have geographic flexibility. Utilities do not.

When AWS faces tough negotiations in Virginia, they explore sites in Ohio, Quebec and Iceland. Utility service territory is fixed by regulatory charter. If the utility becomes difficult to work with, hyperscalers simply build elsewhere. The utility could lose both the load revenue and the demand response capacity.

Tech companies have more information than utilities do.

Amazon knows exactly how much load they'll need in which territory through 2030. They know their workload flexibility down to the minute. They know what the competition in neighboring states are offering. Utilities are negotiating in the dark.

Their switching costs are lower.

A data center can move future capacity to different regions far more easily than utilities can adjust their grid infrastructure.

They coordinate; utilities don't.

AWS, Microsoft and Google talk to each other (don’t believe anyone who says they don’t). They know what deals others are getting. Meanwhile, utilities negotiate in isolation. Interstate coordination is minimal. This asymmetry in information-sharing favors the data centers even if an RTO claims they have it under control.

Most importantly: Tech companies are optimizing globally. Utilities are optimizing locally.

When AWS decides where to locate their next gigawatt of capacity, they're comparing offers from 50 utilities across 12 countries. Any given utility is trying to keep one large customer happy. They have options. You and your team are busy preparing for a quarterly report and an upcoming utility commission meeting.

The 2029 scenario: When leverage inverts

Let's return to that August 2029 phone call. But this time, imagine it goes differently.

Your RTO calls AWS and says, "We need you to curtail 1,000 MW."

AWS responds: "Our demand response contract allows us three refusals per year. We've used zero so far. We're invoking one today. We have critical AI training runs that can't be interrupted because our customer contracts are on a firm deadline."

What's your move?

You could threaten to cut their power involuntarily. But that triggers a force majeure clause in their demand response contract, voiding their obligations for the remainder of the year. You lose access to their flexibility for all future peaks this summer.

You could offer to pay them more. But they know you're desperate. The price skyrockets. What was a $50 million annual contract suddenly costs $200 million for a single month in one summer. Your CFO is furious. Regulators question why ratepayers are subsidizing Amazon.

You could let rolling blackouts happen. Hospitals, homes and businesses lose power. The political fallout is unprecedented. Your CEO testifies before the state legislature. Heads roll.

This is the hostage situation. And here's the uncomfortable part: AWS isn't being malicious. They're honoring their contract, which allows refusals. They're serving their customers who have uptime requirements. They're operating rationally.

You're the one who designed your grid to depend on their voluntary cooperation.

A framework for today

The good news is we're not in 2029 yet. Utilities and regulators still have time to structure these relationships differently. Here's what that might look like:

First, mandate reserve margins that don't count demand response.

When calculating your planning reserve margin, exclude data center demand response from your firm capacity. Treat it as a bonus, not a crutch. Yes, this means building more traditional generation and storage. Yes, it's more expensive upfront. But it prevents the dependency trap.

Thinking about your next integrated resource plan? Assume zero data center demand response when planning capacity requirements, even though you have contracts for gigawatts of it. Any DR that materializes is surplus protection, not baseline reliability.

Second, structure contracts with minimum participation floors

Don't accept contracts that allow unlimited refusals. Instead, require that data centers must provide demand response for some firm percentage of grid emergencies (maybe 75% is a good number), defined by specific criteria like temperature, load or grid stability thresholds. Build in financial penalties for non-performance that actually sting.

For example, Georgia Power's recent tariff updates for large users, including major hyperscalers, include a "reliability credit" mechanism: The data center gets paid less for non-compliance and refusing some number of curtailment requests per year. This could align incentives properly.

Third, create mutual dependency, but make it explicit.

If data centers want preferential power rates or expedited interconnection, they should trade something valuable: firm curtailment commitments that go on their balance sheet as an obligation, not an option.

Some utilities might experiment with "capacity credit agreements" where data centers receive partial ownership of the demand response value they create. But in exchange for this, they accept mandatory curtailment during defined emergency conditions. This would transform demand response from a voluntary program into a contractual obligation with teeth.

And fourth, invest in real alternatives.

The only way to negotiate from strength is to have genuine alternatives. That means:

- Build storage. Yes, battery prices are falling rapidly. A 1,000 MWh facility can provide the same peak-shaving as data center demand response and you control it absolutely. But do not ignore complementary pathways that leverage onsite fuel storage.

- Invest in distributed energy resources. Aggregated residential solar, batteries, backup gensets at commercial and industrial locations, and smart thermostats are slower to deploy but they can't move to another state.

- Maintain peaker capacity. Yes, it's expensive. Yes, it sits idle most of the year. But it's insurance against dependency. Some insurance is worth buying.

The utilities in the strongest position in 2029 will be those who built redundant flexibility into their systems today, even when the spreadsheet says demand response is cheaper.

The uncomfortable conversation we need to have

Here's what I tell utility executives in private: You're not just negotiating power contracts. You're negotiating the future governance (and even ownership) of critical infrastructure.

State regulators need to ask harder questions: What happens when a data center's financial interests conflict with grid reliability? What if AWS is facing a quarterly earnings call and can't afford the revenue hit from curtailing operations? What if a foreign adversary posing as a customer offers a data center operator $2 billion to refuse curtailment during a critical moment?

These are not paranoid scenarios. They're basic game theory once dependencies become asymmetric.

I'm not arguing against data center demand response. It's a valuable tool. But "valuable tool" and "critical dependency" are different things. The distinction matters.

We need demand response contracts structured like insurance policies, not hostage negotiations. We need utilities to maintain optionality even when it's expensive. We need regulators to require that grids can function without data center cooperation and to treat any cooperation as a bonus, not a necessity.

Most importantly, we need to have this conversation now, in 2025, when we still have choices. Because by 2029, the dependencies will be locked in. The infrastructure will be built. The contracts will be signed. And utilities will be making phone calls to tech executives, hoping they agree to keep the lights on.