Dive Brief:

- The House Energy and Commerce Committee voted unanimously Thursday to advance a five-year extension of federal weatherization and energy upgrade assistance while raising the average subsidy per housing unit from $6,500 to $12,000 for low-income households.

- The bill funds weatherization assistance at $350 million per year and establishes a $250 million “weatherization readiness program” to prepare homes for efficiency upgrades.

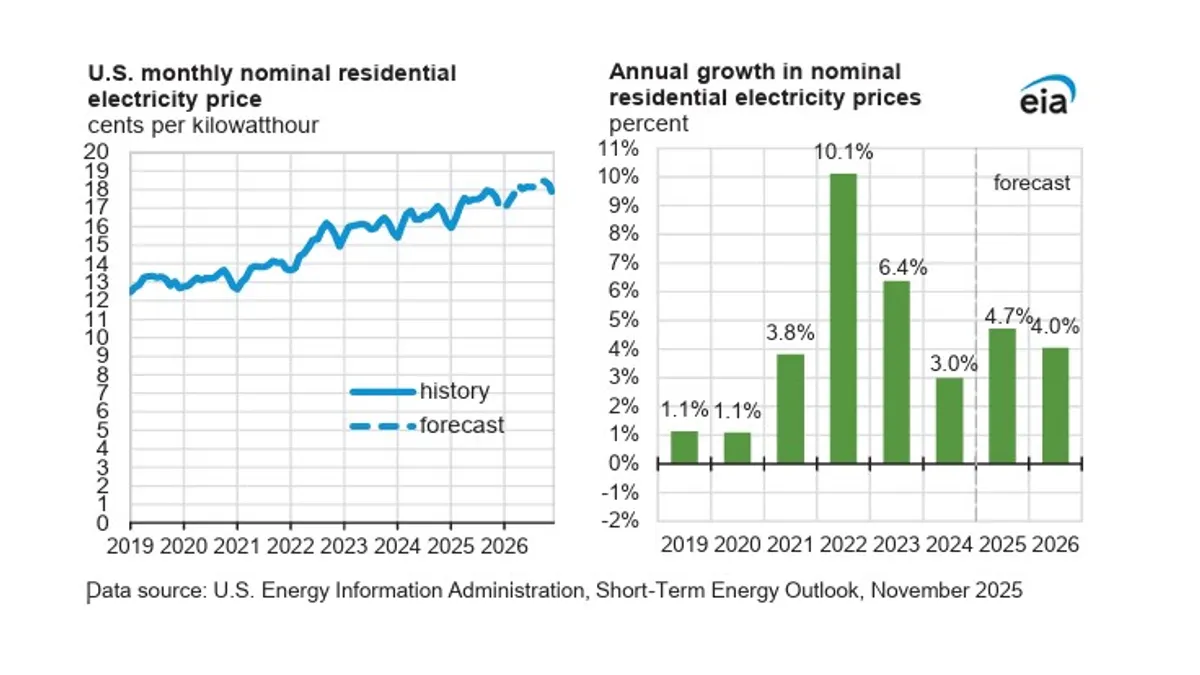

- New York Rep. Paul Tonko, the bill’s top Democratic sponsor, said in a statement that weatherization could check rising electricity prices and improve beneficiaries’ quality of life. “We know weatherization works, not only serving to lower energy costs, but also making homes healthier and safer,” he said.

Dive Insight:

Tonko’s bill reauthorizes the long-running Weatherization Assistance Program, which dates to 1976. Tonko said the subsidy increase would support more efficiency upgrades for each household and ensure competitive pay for the workers performing them.

The newly-created readiness program would direct grants to state and tribal governments to help low-income households address structural, plumbing, electrical, roofing and environmental issues in their homes before they receive energy-efficiency upgrades covered under the weatherization assistance program.

Those proactive measures could “reduce the frequency of deferrals of such weatherization measures when the condition of a dwelling unit renders delivery of weatherization measures unsafe or ineffective,” the bill says.

The bill also strikes a $3,000 limit on financial assistance for residential renewable energy systems.

Households at or below 200% of the federal poverty line are eligible for financial support through the Weatherization Assistance Program. The program covers both homeowners and renters making improvements with landlord permission.

Cutbacks in energy efficiency, decarbonization support

Tonko’s bill advanced out of committee as some state and federal agencies are dialing back support for energy efficiency and decarbonization.

On Thursday, the U.S. Department of Energy rescinded the national definition of “zero emissions” buildings established under the Biden administration and removed references to what it said was a “discretionary” standard from its website. DOE will no longer offer technical assistance on the standard, it said.

Lou Hrkman, principal deputy assistant secretary for critical minerals and energy innovation at DOE, said in a statement that the “arbitrary and imprecise federal guidance” would complicate buildings’ interactions with the U.S. energy system. He advised state and local governments to disregard it.

Meanwhile, in Arizona, state regulators voted to halve Arizona Public Service’s annual energy efficiency budget. The $40 million allowance is less than half APS’ initial request and about 50% less than the previous funding level of $79.4 million. It zeroes out funding for energy audits in existing homes, suspends funding for energy-efficient new construction and reduces funding for efficient HVAC systems in commercial and industrial buildings, according to an analysis from the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project.

At an open meeting Thursday, Arizona Corporation Commission Vice Chair Nick Myers said residential energy-efficiency investments were far less cost-effective than other measures to boost grid capacity. Residential energy efficiency costs Arizona about $441,000/MW per year, a fraction of the lifetime capital and operational cost of a new gas-fired power plant, he said.

Myers said Arizona’s largest electric utility should instead develop a unified, sophisticated virtual power plant knitting together its existing demand-side management initiatives.

“I want to see APS … bring forward a more cohesive virtual power plant strategy, one that possibly consolidates the individual programs we’ve been treating as separate silos,” he said, referring to the utility’s air conditioning load-shifting, commercial and industrial demand response, managed electric vehicle charging and energy storage programs.

A VPP “should operate as a true grid asset, one capable of delivering firm capacity, supporting reliability events, and reducing the pressure on ratepayers to build traditional generation or wires solutions prematurely,” Myers added.