Matthias Fripp is director of global policy research and Brendan Pierpont is director of electricity modeling at Energy Innovation.

The U.S. Department of Energy recently issued a report warning that if aging power plants retire as planned, much of the country could face hundreds of hours of blackouts annually by 2030. This outlandish claim is built on a deeply flawed analysis: the DOE assumes that the power sector will stop building new resources after 2026, even as demand rises and old generators retire. This defies how utilities and grid operators actually plan for future needs, and could result in higher utility bills for Americans.

Supply and demand, without the supply

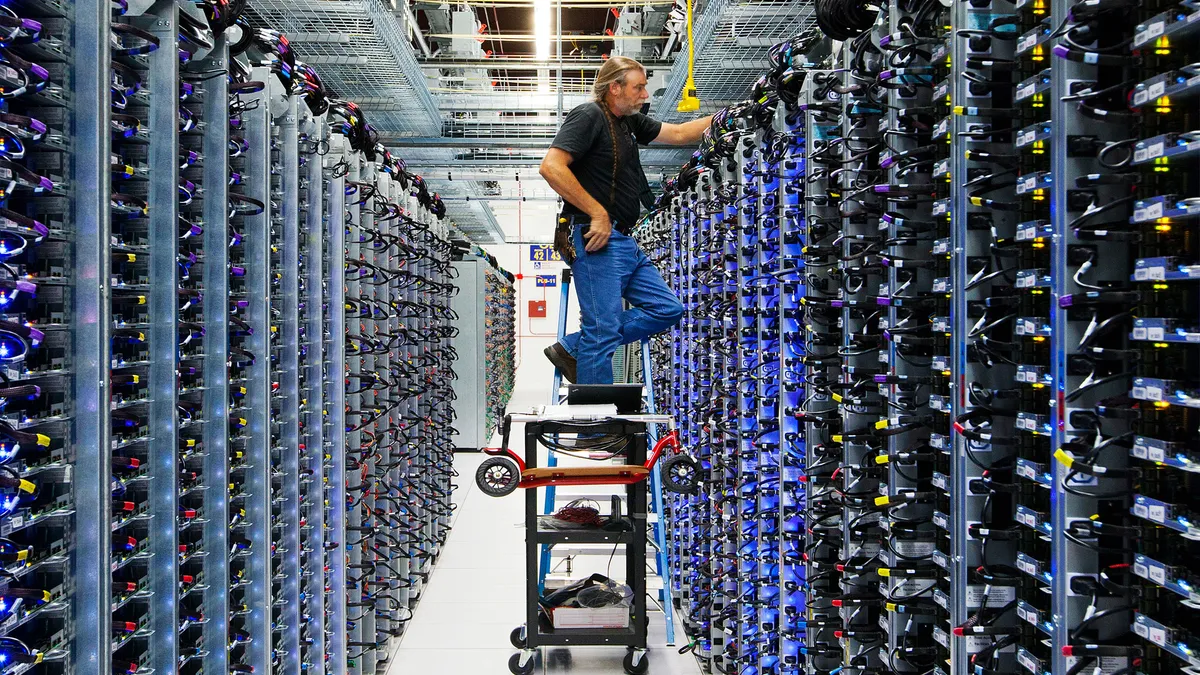

There is no question that electricity demand is growing faster than it has in decades, and utilities and grid operators around the country are meeting the moment with plans to build more and faster. The DOE’s analysis uses aggressive but plausible forecasts for electricity demand growth from data centers and other drivers, and potential retirements of aging generators.

But unlike any actual utility planner faced with rapidly growing grid needs, the DOE assumes the U.S. power sector will effectively stop building new resources after 2026. It does this by only accounting for those projects already under construction or with signed contracts. This paints a distorted picture of the grid in 2030: a gap between supply and demand so large that widespread shortfalls are a foregone conclusion.

Keeping zombie power plants online

Earlier this year, the Trump administration issued “emergency” orders to keep the J.H. Campbell and Eddystone power plants open — plants that are so expensive and unreliable that their owners had decided it was time to shut them down. These orders, however, were not based on a credible reliability need. Dan Scripps, chair of the Michigan Public Service Commission, was quoted as saying, “The grid operator hadn’t asked for this, the utility hadn’t asked for this, we as the state hadn’t asked for this ... We certainly didn’t have any conversations with the [Energy Department] in advance of the order, or since.”

The DOE’s new report lays the groundwork for the administration to strong-arm states into propping up uneconomic power plants nationwide. This would be a costly mistake for America, raising power bills without improving grid reliability.

After ignoring the plans and markets that drive new supply, the DOE report considers only one reliability solution. The report evaluates a scenario where 104 GW of faltering coal and gas plants stay online past their planned retirement dates to fill the artificial gap that the report itself created. However, the owners of these aging plants plan to shut them down for a reason. Many are too expensive to keep online and unable to compete with newer, cheaper and more efficient resources, even in markets with rising demand and rising prices. In fact, coal’s costs have risen by 28% between 2021 and 2024.

Aging, expensive plants are far from the only way to maintain reliability. Utilities are planning diverse portfolios of wind, solar, storage and gas — portfolios chosen because they are reliable and cheaper. Forcing aging plants to remain online will hike customer bills without improving reliability.

On the other hand, if zombie coal and gas plants displace newer, cleaner and cheaper generation options, they could easily become a liability, with consumers on the hook for most of the risk. Some coal plants have seen coal piles freeze during extreme cold weather. Others face maintenance challenges, environmental compliance costs, or high outage rates. Keeping them on life support doesn’t guarantee performance during grid emergencies and could, in fact, risk shortages if they block newer, more reliable options, including siting new resources at existing plant sites.

Utilities and grid operators are already planning for reliability

Utilities, regulators and grid operators know how to keep the lights on, but the DOE report seems to ignore that fact.

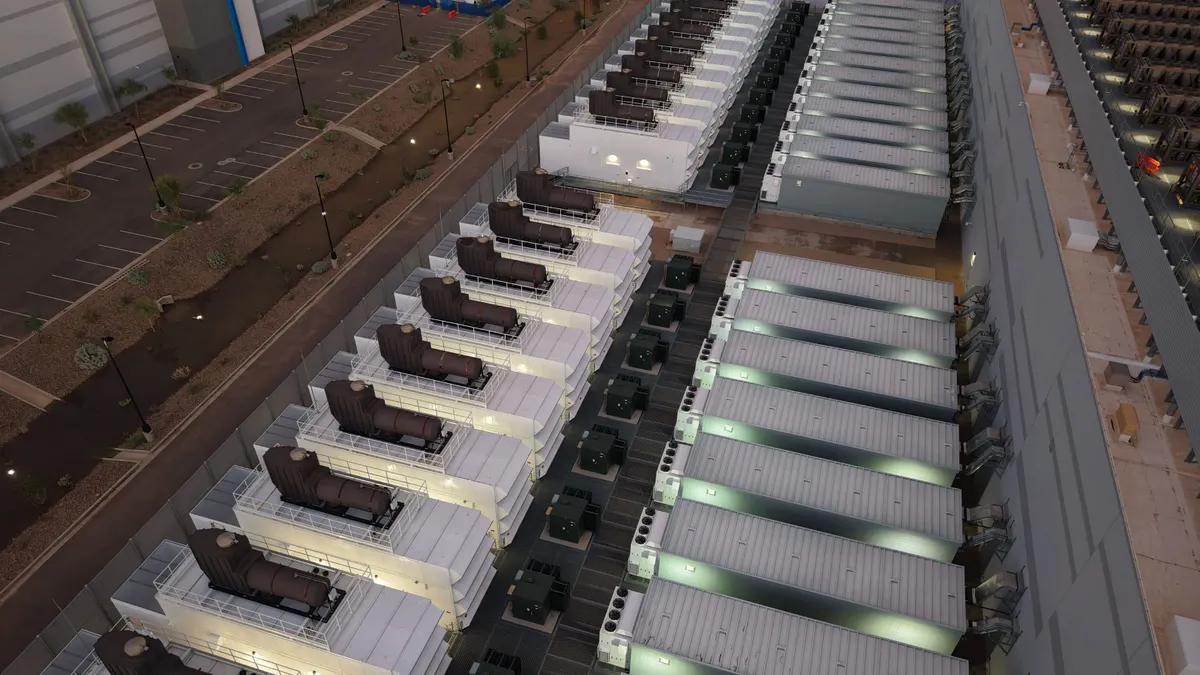

Around half of U.S. electricity demand is met by utilities that develop long-term resource plans, often required by law and overseen by state regulators. Utilities conduct detailed analysis to make these plans, evaluating dozens of potential resource portfolios to select resources that meet reliability needs at lowest cost to customers. Solar, wind, battery energy storage and natural gas feature heavily across these plans. According to EQ Research, by 2030 these utilities plan to build nearly twice as much gas and battery capacity as the DOE assumes will come online by 2030 nation-wide. And that’s just one half of the nation’s grid.

In other regions, utilities don’t conduct long-term resource planning. Instead, market mechanisms reward new resources for being built when needed. The DOE undercounts potential additions in these areas, too. In Texas, the DOE report includes just 17 GW of new batteries and less than 1 GW of gas by 2030 — despite 37 GW of new batteries and gas with signed interconnection agreements and another 199 GW of batteries and gas in the interconnection queue. In the nation’s largest electricity market, the PJM Interconnection, prices rose in the capacity market this year, sending the signal for developers to build more resources. Yet the DOE’s analysis pretends growing demand cannot trigger new supply, ignoring the basics of competitive markets.

The DOE’s study simply ignores the extensive planning efforts of regulated utilities and the robust pipeline of projects in market-based regions. These mechanisms are not hypothetical — they have delivered reliable power for over a century and are actively guiding hundreds of new projects every year.

In effect, the report assumes everyone involved in maintaining grid reliability — utilities, regulators and regional markets — will fail spectacularly at the task they care about most: keeping the lights on.

The DOE report even acknowledges this disconnect, admitting “entities responsible for the maintenance and operation of the grid have access to a range of data and insights that could further enhance the robustness of reliability decisions.”

In other words, regional planners are already doing this work.

Reliability is a team sport

Meeting growing demand from data centers, manufacturing and electrification requires grid solutions that are reliable, affordable and clean. Wind, solar, storage and some flexible gas are the technologies that regional utilities and markets have chosen for this task. They are cost-effective and work together to create a seamless, reliable power supply.

Using the DOE’s flawed report to justify emergency orders that prop up derelict coal plants would sideline the very institutions that are already delivering reliable power, raising costs with no benefit.

The most effective way to maintain grid reliability is to let planners plan, markets work and utilities build the resources they’ve already identified as the most affordable path forward.

Grid experts know how to keep the lights on. If the federal government wants to help, it should support that process — not override it with faulty assumptions and top-down directives.