This opinion piece is part of a series from Energy Innovation’s policy experts on advancing an affordable, resilient and clean energy system. It was written by Mike O’Boyle, electricity director.

In May 2022, California risked making the same mistake that has plagued United States offshore wind policy for decades — weak ambition.

Under a law requiring the state to set offshore wind planning targets, the California Energy Commission proposed a 10-15 gigawatt goal for 2045, enough to power just 10% of the state’s future net-zero grid.

But thanks in part to a University of California, Berkeley, analysis showing California’s vast economic offshore wind potential, the CEC changed course, setting a 25 GW offshore wind target.

Critics argue the state has no existing offshore wind industry, and the federal government only issued its first lease for wind development off the state’s shores last December. Furthermore, only a handful of floating offshore wind projects, which will be required off California’s steep coastline, operate worldwide.

However, criticism like this uses backward logic. California and America’s lack of an offshore wind industry is the result of uninspiring policy commitments, not the cause.

Earlier this year, I traveled with other Californians to the United Kingdom and Denmark, home to some of the world’s leading offshore wind industries, to learn how they got there and where they’re going.

One Danish expert divulged the state’s 10-15 GW goal would have been insufficient to attract foreign investments in ports and supply chains. It turned out 25 GW is closer to the minimum — but an even bigger goal should be in play for California and other states.

The British and Danish experience offer three lessons: First, offshore wind technology is mature and can be a cost-effective, scalable U.S. resource. Second, transmission planning can make or break affordable, rapid offshore wind deployment. Third, infrastructure and supply chain development will follow ambitious targets, but public investments are crucial to driving private investments.

U.S. offshore wind policy clearly needs an upgrade.

Technology will not be the limiting factor

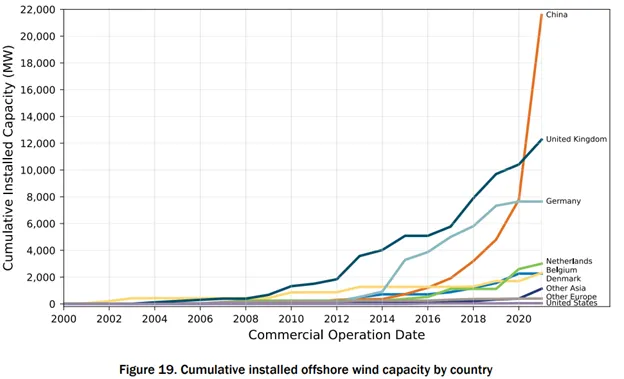

Though the U.S. offshore wind industry is nascent, the global industry is mature. Scale and technology improvements have driven remarkable cost reductions. As of 2021, more than 50 GW of offshore wind have been installed globally, enough to power about 18 million U.S. households. The U.K. installed 2.3 GW in 2021 and Denmark added over 600 megawatts. Meanwhile, China alone installed 17 GW in 2021, adding roughly 50% to the international total.

Turbine size is one reason the technology has gone mainstream — larger blades are driving more consistent energy production and lowering total energy costs. Today, 15-17 MW turbines are the industry standard — five times the power rating of a standard land-based turbine, and three times the output of the 5 MW turbines used for the first U.S. offshore wind farm at Block Island, Rhode Island, built in 2016.

But turbines cannot grow indefinitely. Danish manufacturers indicated that, like the onshore wind industry, offshore manufacturing facilities must eventually standardize production to achieve economies of scale and profitability.

Bigger turbines, mass production, and larger projects have driven major cost declines across Europe. The U.K.’s 2022 offshore wind auction yielded contracts for 7 GW of capacity at an average of $54 per megawatt-hour, down from $147/MWh in 2014-2015.

Nevertheless, wind costs could increase in the near-term due to high commodity prices, high interest rates, and an immature domestic supply chain. Avangrid recently asked Massachusetts regulators to dismiss their 1.2 GW of offshore wind contracts to deliver power by 2028 after it became clear the developer wouldn’t tolerate its current contract price of $72/MWh. However, Europe’s recent cost declines and National Renewable Energy Lab long-term price forecasts indicate these problems should be temporary.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Floating Offshore Wind Shot seeks to reduce floating offshore wind cost by 70%, to $45/MWh by 2035. While most projects are fixed to the seabed (“fixed-bottom”) in shallow waters, floating projects attach to the sea floor with anchors. The U.S. energy industry already knows how to float large oil and gas rigs in deep water.

Deeper waters provide access to the best wind resources. Recent developer interest in California’s offshore lease sales demonstrate floating offshore wind is on the cusp of U.S. commercialization. Floating turbines can also be assembled at ports, reducing underwater noise impacts caused by pile-driving fixed-bottom assemblies.

Scotland boasts one of the world’s first floating offshore wind farms, allowing access to better wind resources and deeper waters. And their offshore wind industry now employs tens of thousands of former oil and gas workers. We’ve seen a preview of this cross-cutting expertise in the U.S. — the Block Island Wind Farm was built by companies with deep experience in offshore oil drilling.

Infrastructure and supply chain will follow bigger offshore wind targets, but public spending is crucial to driving private investments

The Biden administration is targeting 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030, an ambitious but achievable goal. But European targets show we can set loftier objectives beyond 2030 to achieve the scale and supply chains needed for offshore wind to succeed.

The U.K. has a 50 GW target by 2030 — 20 GW higher than the U.S. — but only generates about 8% as much electricity. Denmark is even more aggressive — a 13 GW goal with total generation less than 1% of the U.S. output. To keep pace with these leaders, the U.S. would need to target 600-1,500 GW of offshore wind.

As a result of their targets, these countries are also home to robust supply chains and port infrastructure. The Danish Port of Esbjerg has become a global force in offshore wind, with plans to expand to meet Europe’s offshore wind boom. Though the port already supports more than 1 GW of wind installations annually, a recent Siemens Gamesa contract will dramatically expand its size to help scale the floating and fixed offshore wind industry. Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners’ winning bid in the California auction demonstrates the country is well positioned to export these innovations around the world.

In response to more ambitious European targets, six North Sea ports agreed in 2022 to jointly install 150 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2050. Similar regional targets for East and West Coast ports would rationalize the investments needed to support broader industry growth.

Today’s port infrastructure is insufficient to meet the long-term demand for U.S. offshore wind. East Coast ports lack funding for critical components and would benefit from further research on accommodating future floating offshore wind, bigger deployment targets, or larger turbines. West Coast ports are at the starting line, and scaling up to meet California’s 25 GW goal by 2045 and Oregon’s 3 GW goal for 2030 will require rethinking their port infrastructure. It’ll also require significant state and federal funding, some of which is available from the bipartisan infrastructure law.

How we plan the transmission grid can make or break affordable, rapid offshore wind deployment

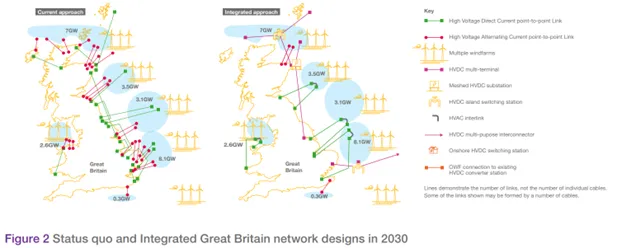

Meanwhile, long-standing transmission issues inhibit a low-cost, reliable transition to a clean grid, including cost allocation, interconnection, stakeholder engagement, permitting and regional planning. Fixing these problems at FERC and the ISO-RTO level will be crucial to offshore wind’s success, but unique offshore wind policies modeled after the U.K. can help.

The U.K.’s National Grid recently proposed a “holistic network design” to reduce transmission costs by $6.5 billion compared with a project-by-project interconnection approach. This could help fix the status quo in the U.S., where individual projects face a growing queue to interconnect and pay for connecting lines one-by-one.

Designing a regional grid fit for the purpose of rapid, low-cost interconnection seems daunting, but it will reduce costs and wait times while helping reach state and federal policy goals.

A recent Brattle Group report offers comprehensive policy recommendations for the U.S. to follow the U.K.’s lead. These include a proactive transmission planning process that will reduce total costs, support future industry growth beyond current targets, and expand onshore interconnection capacity.

Offshore wind is mission critical

Though clear differences exist, Americans can learn a great deal from Europe about how to make offshore wind a core part of our energy transition. This starts with thinking much bigger.

While 30 GW by 2030 is a good start, the U.K., Denmark, and other nations should inspire us to set our sights orders of magnitude higher. Electric vehicles, buildings, industry and synthetic fuels may triple electricity demand over the next three to four decades. We must better leverage our offshore resources if we hope to succeed.