A new kind of energy storage program proposed by Xcel Energy in Minnesota is attracting attention because of the implications for how distribution system resources will be managed – and who will own and control them – as the U.S. power system becomes more decentralized.

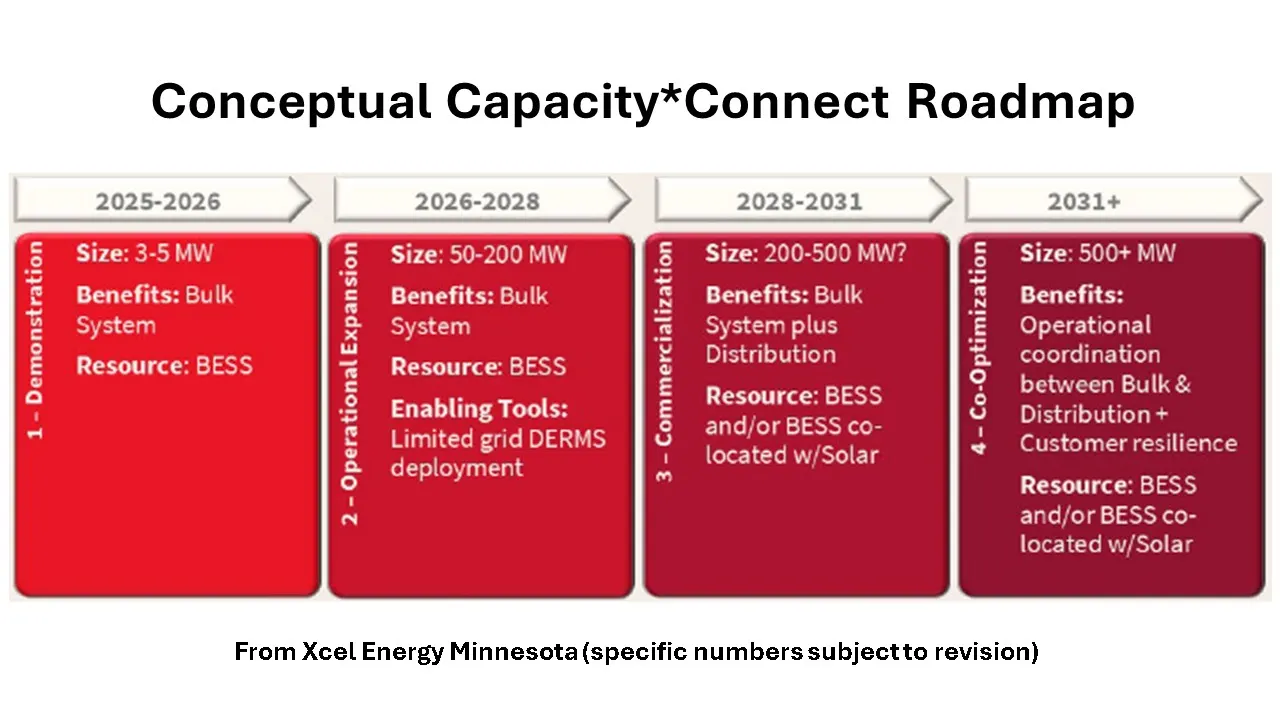

Xcel called its Capacity*Connect, or C*C, pilot a “first-of-its-kind” “distributed capacity” program when it applied for regulatory approval in October from the state Public Utilities Commission.

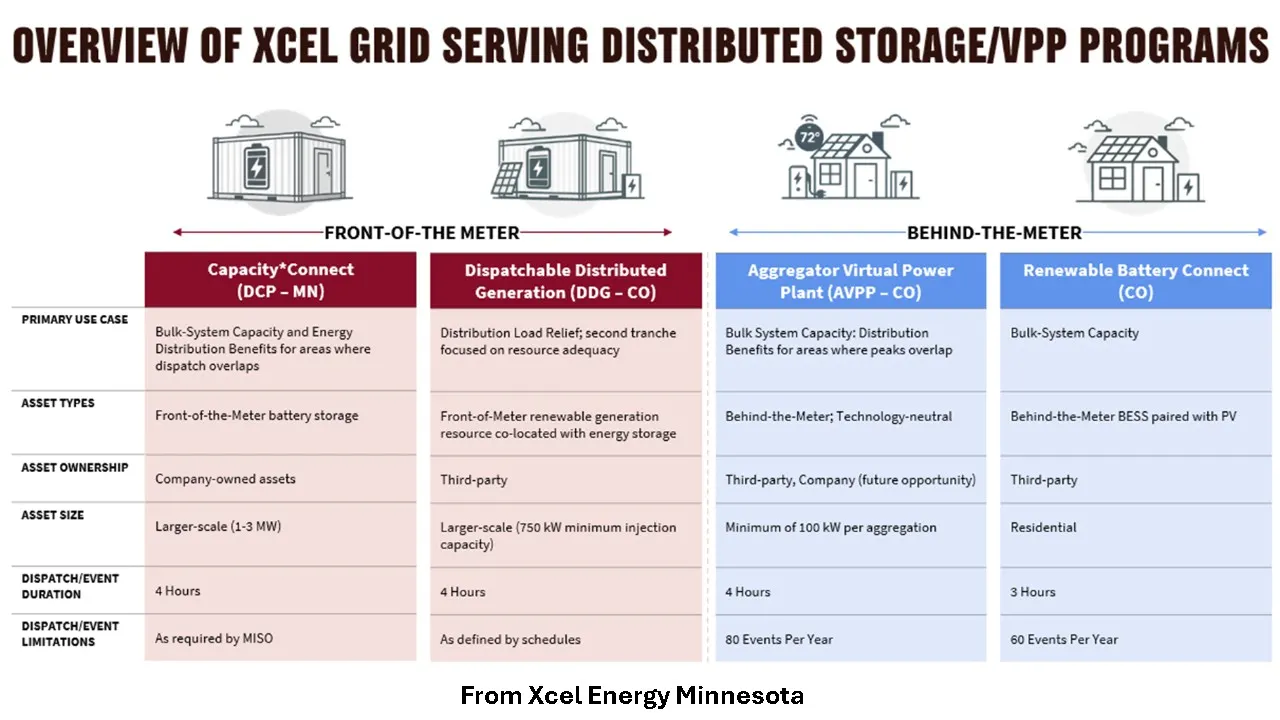

If approved by regulators, Xcel would deploy up to 200 MW of front-of-meter batteries ranging from 1 MW to 3 MW each at “strategic locations” on its distribution network by 2028. Xcel would retain ownership of the batteries and pay third parties to host them on their property. The program has a proposed budget ranging from $152 million to $430 million.

The proposal has been criticized by some stakeholders, particularly aggregators of customer-owned distributed energy resources, who say the utility is engaging in anti-competitive behavior and ratepayers will suffer.

C*C “will be more expensive” and “will not get resources online as quickly,” said Amy Heart, senior vice president of public policy for Sunrun, which operates one of the largest virtual power plants in the US.

But other VPP advocates say utility-owned resources and aggregated customer-owned resources are not mutually exclusive.

“Providers of both business models argue their option can most cost-effectively meet the anticipated load growth and both are right,” said Ted Ko, founder and executive director of the Energy Policy Design Institute, or EPDI. “The type of VPP for a system depends on a granular understanding of the system services that are needed.”

Minnesota regulators are expected to issue a decision on C*C by mid-2026.

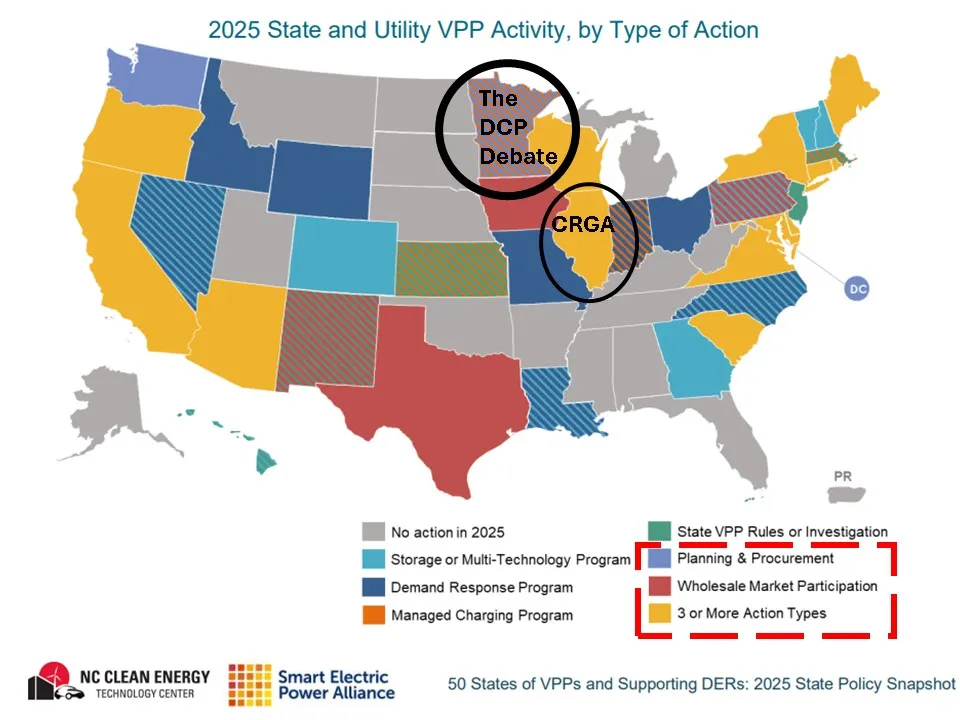

Presently, VPP interest is growing across the country. Some states, like Maryland, Illinois and New Jersey, are requiring utilities to develop programs. Others, like Michigan and New Mexico, are considering laws to do so. The requirements and models vary, which stakeholders say could accelerate innovation or lead to jurisdiction by jurisdiction debates.

Dueling business models

Over 65% of the C*C revenue will come from providing the Midcontinent Independent System Operator with bulk system capacity, also called resource adequacy, Xcel executives said.

Zach Pollock, director of grid strategy and emerging technology for Xcel Energy, said the revenue will benefit all Xcel Minnesota customers.

The batteries will also help meet energy storage needs identified in Xcel’s 2024 integrated system plan, said Lon Huber, Xcel senior vice president, integrated system planning, and chief planning officer. As owner-operator, Xcel is “uniquely positioned to maximize benefits of distribution system storage over the system operator or third-parties,” he added.

The utility is pursuing a different model in Colorado, however. The Active VPP, or AVPP, program, was ordered by Colorado Senate Bill 24-218, Pollock said. Third party aggregators will enroll and manage 25 MW of behind-the-meter, or BTM, customer-owned DER resources per year over five years, he added.

In Maryland, Baltimore Gas and Electric’s DCP proposal awaits regulatory guidelines.

But key aggregated DER performance data will come, by the end of 2026, in Illinois, from VPPs enabled by the 2025 Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability (CRGA) Act, said Scott Vogt, vice president of strategy, energy policy and revenue initiatives with Commonwealth Edison, or ComEd.

Under CRGA’s seasonal scheduled dispatch, utilities will work with aggregator-led VPPs beginning in Spring 2026 to reduce ComEd’s costs in the PJM Interconnection capacity market, said Vogt.

In Minnesota regulatory filings, advocates and opponents detailed their concerns about Xcel’s DCP.

Aggregator-led VPPs

The Illinois and Colorado programs will be led by aggregators and demonstrate what is possible without utility ownership, Sunrun’s Heart and other solar advocates said.

“The most cost-effective way ComEd can quickly ensure meeting its summer peak demand is by using distribution system resources,” Vogt said. Participating customers will be compensated this year with an upfront enrollment rebate and a nominal annual participation payment, which the utility will recover through rates, Vogt said.

Benefits from reduced system-wide capacity costs for all customers will not be allotted until PJM’s 2029-2030 forward capacity auction, Vogt said. They will be delayed by the regulatory and accounting complexities of working through MISO markets, he added.

ComEd is not considering the Minnesota C*C business model, because “Illinois regulation does not provide a clear direct path to utility asset ownership like other states.” Vogt said.

Cost-benefit differences

The cost-effectiveness of Xcel’s C*C is a key point of debate.

Its estimated price, according to a filing by solar stakeholder groups, will be $2,150 per kW for 200 MW. Xcel Colorado's aggregator-led AVPP program will cost an estimated $624 per kW for 125 MW, the filing added.

Aggregator-led VPPs and pilots in 22 states have had industry-estimated benefit-to-cost ratios higher than the 0.68 estimate for C*C, another solar parties filing said.

And Xcel did not quantitatively compare “the costs and benefits of utility ownership to the costs and benefits of customer or third-party ownership,” a Minnesota Attorney General December 10 filing added.

But the C*C proposal did provide the ordered “qualitative” analyses of the utility-owned DCP and “customer-owned and third-party owned resources,” Xcel’s initial filing said. A quantitative analysis was not required, and Xcel does not have access to third-party cost structures and ownership models, Xcel added in an email.

The CRGA legislation and the Colorado legislation exclude utility-owned DER for a reason, said Sunrun’s Heart. The DCP is “a short-sighted program that is slower, less effective, and will ultimately be more expensive for ratepayers,” she added.

Comparing costs and benefits of the “fundamentally different” Minnesota and Colorado programs is a mistake, Pollock said. The Colorado program cost is based on five years of payments for use of customer-owned assets, while C*C’s large-scale batteries are 20-year utility assets, he added.

“It is not clear that one type of flexibility has a better cost benefit than the other,” said Brian Seal, principal technical director and lead for the DER integration Flex-It Initiative for the Electric Power Research Institute, or EPRI. Based on his own many cost-benefit studies, “it depends on the specific type and number of technologies,” he added.

Large-scale batteries typically serve consistently up to 20 years, while consumers do not make “long-term commitments” to aggregation programs, Seal said. In addition, availability of BTM DER aggregations varies as weather, season, time of day, and consumer “interest and willingness” change, he added.

The competition objection

Another key point of debate over C*C is that “it does not work with the competitive market,” Heart said.

The R Street Institute filing by former Minnesota commission staffer Chris Villarreal, now associate fellow and consultant with the R Street Institute, agreed.

System services “are generally put out to bid by utilities because many regulators see the value of learning market prices,” Villarreal told Utility Dive. A competitive procurement “introduces cost discipline,” which is especially important because “utilities have a bias toward capital investments,” he added.

Xcel Minnesota’s work with Sparkfund to competitively procure hardware and development services is not the same as bidding to meet system needs, Villarreal said. That would require a technology neutral competitive solicitation for distribution capacity, or at least for competitors with Sparkfund to act as implementer of the DCP, he added.

“Xcel’s sole-source selection of Sparkfund to run C*C could be using ratepayer money to bolster Xcel’s unregulated investments,” the Attorney General’s January 27 filing added.

Finally, Xcel’s claim that utility ownership is the only way to protect reliability and cybersecurity is misleading, Villarreal said. Xcel can state its needs for situational awareness and include them in market bidders’ contractual obligations, he added.

“Utility ownership also risks the utility preferring its own resources, which distorts the market,” said Kay Aikin, founder and CEO of software platform provider Dynamic Grid. “It also will be more expensive than aggregations of customer-owned DER because Xcel gets cost recovery and Sparkfund gets a profit margin,” she added.

“The C*C program was “conceived and developed” with Sparkfund in 2024, Xcel’s January 9 filing acknowledged. And Sparkfund is owned, along with over 100 other companies, by venture capital fund Energy Impact Partners, in which Xcel’s corporate parent is a minority investor not involved in portfolio company operations, the filing added.

Because of Sparkfund’s innovative approach to the DCP, Xcel did not pursue other program implementers, its filing said. Sparkfund will locate and develop C*C, and 80% of the hardware and services will be selected through competitive bidding, though operational complexities preclude third-party aggregator participation, the filing added.

For C*C, “varying use cases,” and “third-party ownership [are] premature,” but “C*C will not replace or preclude third-party DER programs,” the filing said. Integrating a grid DER Management System will maximize the use of “existing infrastructure … as we advance toward more dynamic operations,” and a “broader ecosystem of DER initiatives,” it added.

C*C will, where possible, be located to avoid negatively impacting the hosting capacity needed by DER aggregators, the filing said. “A core tenet of the program is to stack benefits where possible,” which is why C*C’s projected benefits “should not be seen as a ceiling,” it said.

Colorado legislators mandated working with third-party aggregators and customers, Sparkfund CEO Pier LaFarge said. Xcel “seems to want to scale and mature both business models to see how their values may fit together to put downward pressure on rates and serve load growth,” he added.

The BTM DER “superpower is that customers want them, and it would be ridiculous to ignore those thousands or millions of assets,” LaFarge said. But “utility-owned batteries, like utility-owned transformers and substations, can be built where needed and dispatched without concerns about customer participation,” he added.

Both have “excellent value propositions,” LaFarge said. The DCP program is “a new way for Xcel Minnesota to expand its distribution sited capacity,” he added.

A DCP could lead to a utility-led “bring your own offsite flexibility resource” program, LaFarge said. That would allow big energy users to pay for customer-owned DER managed by aggregators instead of developing onsite generation or curtailing usage, he added.

Utilities’ operational excellence is needed, Dynamic Grid’s Aikin said. With growing electricity demand and increasing costs for distribution system renovation, “every utility should be developing price signals and using developers of VPPs and of batteries,” she stressed.

Room for both

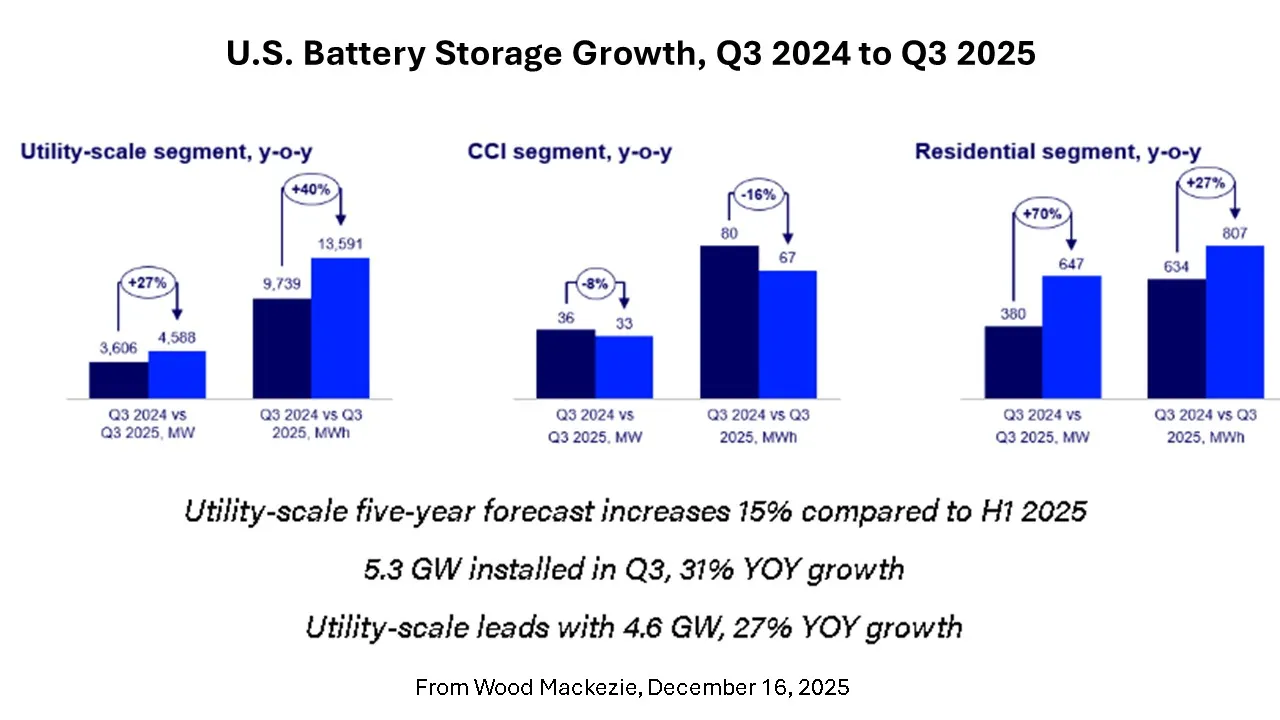

The installed capacity of utility-scale batteries like those to be used in C*C grew 4.6 GW, or 27%, from 2024 to 2025, Wood Mackenzie data shows. But residential batteries like those in DER aggregations grew, too, by 70%, or 647 MW, the report added.

“The two types of VPPs are “complimentary,” EPRI’s Seal said. For a specific need like a load growth surge, “it is difficult to ensure thousands of customer devices can be enrolled quickly enough,” but if the need is “a slowly emerging issue like load growth approaching an infrastructure limit, it can be met equally well by the utility or a third party,” he added.

Current customer-owned DER aggregations, while valuable, are not yet as fully dispatchable as power plants, according to the Huels Test evaluation developed by DER management software provider EnergyHub. Utilities can, however, readily dispatch large batteries to reduce electricity usage, analysts and stakeholders agreed.

“VPPs alone are not the answer,” Xcel’s Huber said. “But VPPs of all types, like DCP, plus new large-scale generation and transmission, flexibility in large batteries and customer-owned resources, and demand response programs can meet the coming gigawatt-scale growth,” he added.

Regulatory decisions should be based on specific needs and “one regulatory decision does not set the rule for all VPPs,” said EPDI’s Ko. “The long-term vision is for regulators to understand the value in each business model and have all DER compensated appropriately for all the services and benefits they deliver.”