Tim King is president and managing director of Nexans North America.

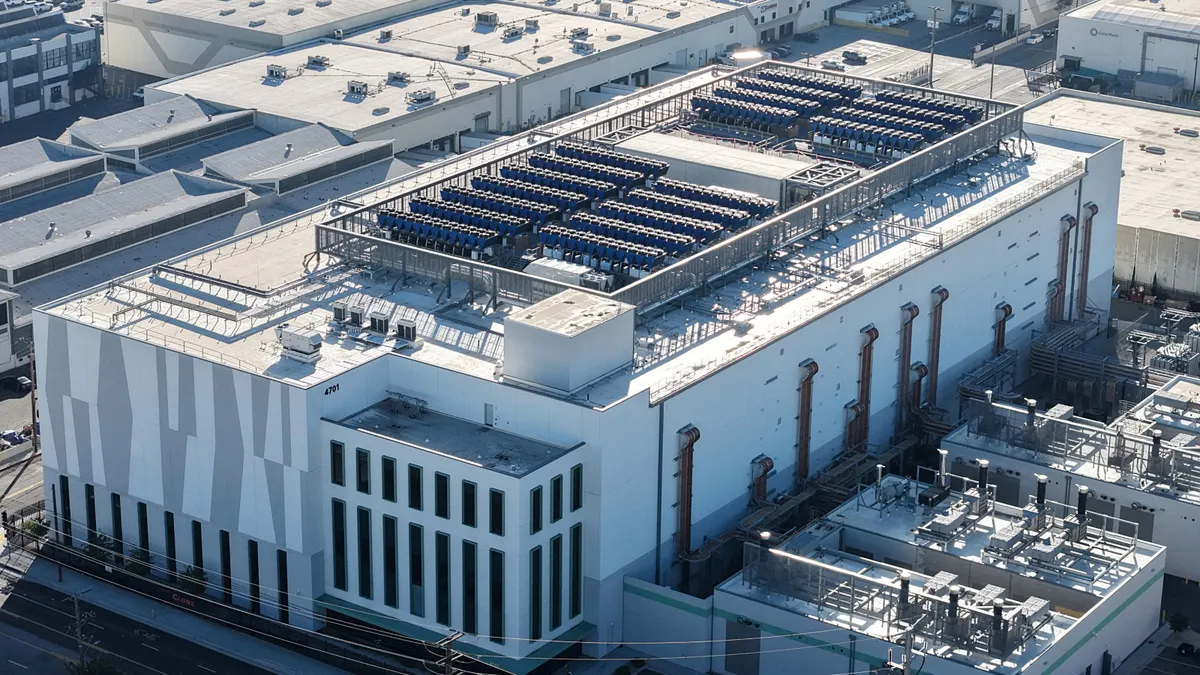

The speed of datacenter deployment has shocked the world. Recent reporting shows a potential underestimation of datacenter proliferation. The 54-volt in-rack power distribution systems supporting current growth were designed for kilowatts, not megawatts. Nvidia and partners including Schneider, ABB and Eaton are addressing this by developing 800-volt DC sidecars to deliver energy for next-generation data centers, but power demands show no sign of slowing.

According to Moore’s law, the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. For years, power draws declined under Dennard scaling: power density stayed constant as transistors shrank. That relationship has broken down and as transistor counts increase, total chip power consumption continues to rise.

The electrical grid is completely unprepared to handle the energy needed to support this datacenter growth. By 2030, it is estimated that approximately 27% of all datacenters expect to run entirely on on-site generation to support this massive influx of power, but that still leaves the other 73% that will be tied to the electrical grid; traditional forecasting will not suffice. The grid needs more generation, quickly, but transmission remains the largest hurdle to reliability.

According to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s data from 2024, more than 2.6 TW of proposed generation and storage are queued up to be added to the US grid. The current U.S. grid has roughly 1.2 TW of installed capacity — less than what’s already in the backlog. And that’s not enough.

Utilities want to invest. They want to expand the grid to stem the oncoming tide, but there are massive regulatory and economic hurdles to jump. The major hurdle: permitting.

The transmission systems in both the U.S. and Canada were built as regional networks, not as a fully integrated continental grid. Transmission lines cross state and provincial borders, and across independent system operator and regional transmission organization lines. This has resulted in a permitting process that is long, convoluted, and takes, in some cases, dozens of permits which could include federal, state, tribal and even local permits for land use and zoning.

This process can take years, threatening economic viability. The only real way to solve this is comprehensive reform with clear leadership. This is exactly what FERC attempted in July 2023 in order to “reduce backlogs for projects seeking to connect to the transmission system and ensure access for new technologies.” Unfortunately, we need it faster than we originally believed.

On top of permitting, new transmission lines must also go through extensive environmental review and are often met with litigation, which makes the timelines ultimately unpredictable. States even block transmission lines running through their states because they don’t wish to subsidize another state’s economic development.

The second issue is generation itself. While 27% of datacenters are projected to have on-site generation, the power needs to be created elsewhere and transmitted via the grid for 73% of new datacenters, which can disrupt the power networks for cities and towns in more ways than one.

For one, who is paying for all of this new infrastructure and why? It’s clear that states and provinces will have a problem with their ratepayers footing the bill for the datacenters that will enable the AI revolution, especially if their livelihoods don’t depend on AI.

It is becoming more clear that our lives are going to become increasingly dependent on AI even if we don’t use it ourselves. Our transportation, grocery stores, computers — everything will have a backbone that is driven by AI. It will eventually become a necessity, not because it is anyone or any company’s individual choice, but simply because it will become pervasive in everyone’s lives. Imagine living today without a cell phone or a car. Technology drives changes in needs.

The other major disruption will be generation. We need to produce more electricity to keep up with the demand from AI. The problem that we are facing, aside from the long interconnection queues from existing generation, is that even if transmission queues were not a problem, the time it takes to build generation is almost as long and in some cases as long as building the new transmission lines.

The average time to build and connect a nuclear plant is nearly a decade. Natural gas and onshore wind, as well as other renewables, take less time to deploy at scale as a response to immediate demand, but are facing interconnection problems and supply chain backlogs. I have seen these backlogs and challenges in the supply chain first hand with both copper and aluminum and have had to react in real time to the challenges presented with tariffs.

There are a few steps that can be taken in the meantime by utilities and developers to move the conversation forward.

The first is to more frequently scan capacity constraints to see what can be upgraded without wires and where efficiencies could be found without major infrastructure changes. The second would be to work with regulators on solving the permitting problem, and fast. There needs to be unification between the hyperscalers, governments and the private sector if we are going to be able to get ahead of this demand. If collectively, we can plan transmission ahead of generation, then we may be able to avoid possible reliability problems. Finally, to prepare for the much-needed generation and transmission, utilities can start to pull forward procurement timelines by locking in long-lead equipment orders earlier.

There is a major opportunity here for utilities, suppliers, regulators and datacenters to work together to build a better electrical grid. The priority is to create a grid that serves everyone equally and economically, while also not reducing reliability. I’m optimistic about what we can accomplish together in this new era.