Energy infrastructure permitting reform is unlikely to clear Congress before late next year, if at all, political and industry observers say. This is despite recent movement on the SPEED Act, which passed the House of Representatives last week.

The permitting reform bill needs 60 votes to pass the Senate, where Republicans hold a slim majority, and any changes would have to go back to the House for approval. In the meantime, a temporary funding deal keeping the government open expires Jan. 30. With that, and midterm elections fast approaching, lawmakers’ bandwidth for negotiating ambitious, long-term reforms is limited, analysts say.

Still, bipartisan concerns about energy affordability and economic development tied to artificial intelligence lend the issue more urgency now than during previous attempts at permitting reform.

“When you consider the importance of the issue, and that it's hard to get anything ambitious through Congress, it's very exciting that we have a 20% to 30% chance, maybe, of getting a significant permitting and transmission package through,” said Devin Hartman, director of energy and environmental policy at the R Street Institute, a free market-oriented think tank.

“That's an oddly exciting probability range,” he added.

Disputes over permit ‘certainty’

The House on Thursday passed the Standardizing Permitting and Expediting Economic Development Act on a 221 to 196 vote, with 11 Democrats joining in support and one Republican voting against it.

The bill would revise the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires federal agencies to assess how their actions affect the environment, according to a summary of the legislation. The bill would change the processes agencies use to comply with NEPA and how courts are allowed to review NEPA-related lawsuits in ways designed to help speed up permitting for pipelines, transmission lines and other energy infrastructure projects.

The bill’s final steps through the House previewed some of the challenges permitting reform faces.

For one, the bill includes “certainty” provisions that aim to prevent agencies from revisiting permits after they are issued. The Trump administration has moved to revoke permits for offshore wind projects this year, raising concerns among a broad swath of elected officials and industry leaders about future presidents using unilateral action to block disfavored projects.

Those provisions, however, drew a backlash from some Republicans. The bill was changed on the House floor so that the legislation wouldn’t affect actions the Trump administration takes before the bill’s enactment into law.

In addition to targeting offshore wind, the administration has introduced new layers of approval for solar and on-shore wind and taken steps to further advance fossil fuels and nuclear power, including in areas they were previously blocked, like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the California coast and the eastern Gulf Coast.

The Trump administration’s efforts to stifle renewables also could make it harder to advance permitting reform in the Senate.

Effectively, there is a ban on solar development on federal land, driven by Trump executive orders, according to Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawai’i.

“In order to get permitting reform, we need to have some confidence that we're not going to make the world safe for the American Petroleum Institute and not for all these solar projects,” Schatz said Dec. 10 during an interview with Axios. “We've really got to address this national solar ban before we get into ... reconfiguring NEPA.”

Also, the SPEED Act fails to address transmission development, Schatz said.

Senate outlook

No major permitting reform bill has been introduced yet in the Senate this session. Legislation is expected to come from the Senate Energy and Natural Resources and Environment and Public Works committees.

Senate legislation will likely include components beyond those in the SPEED Act, such as measures focused on transmission, geothermal projects, the Clean Water Act and critical mineral mining, according to Xan Fishman, vice president of the energy program at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

“I'm pretty optimistic that, like in January or February, we'll see something come out of the key committees in the Senate,” Fishman said in an interview. “There will be a broader deal than just what's in the SPEED Act.”

Potentially, a bill could be signed into law in the second quarter of 2026, he said.

The outlook for permitting reform has improved since the last serious attempt — the Manchin-Barrasso bill, which passed the Senate and died in the House in 2024, in part because of a shift in support from Republicans for transmission development, Fishman said.

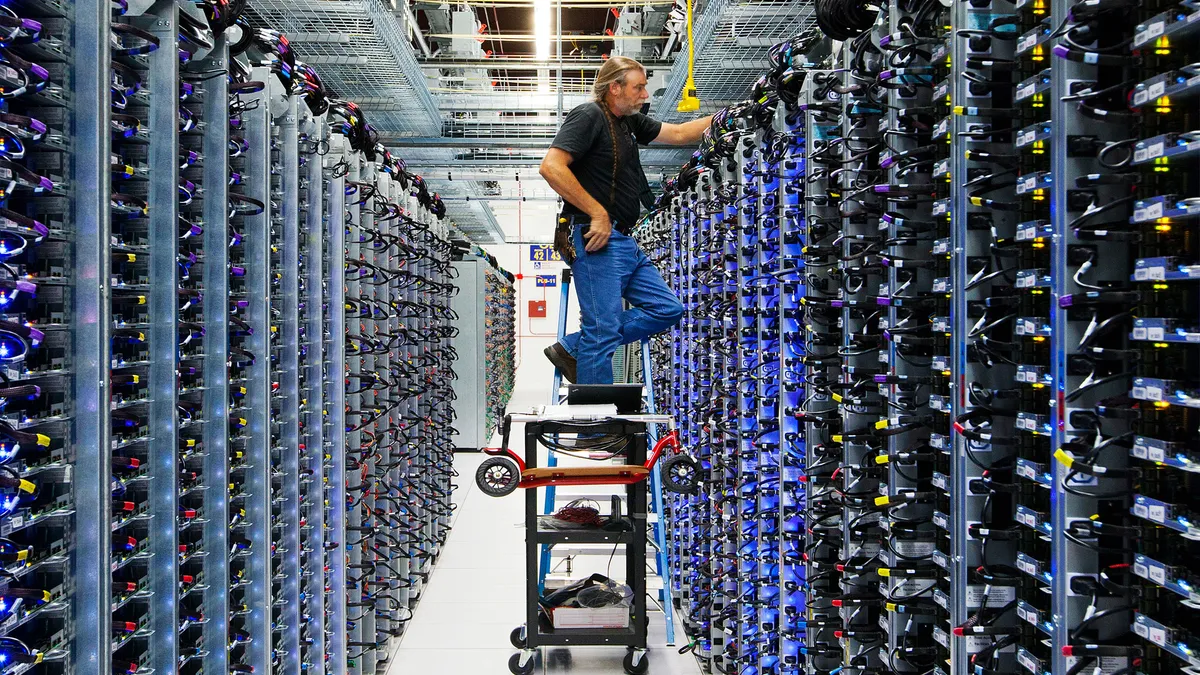

Republicans opposed transmission development at the time as a boon to renewable energy developers, but now they generally view transmission as needed for grid reliability, facilitating data centers and helping lower power prices, he said.

“If we don't get this right … electricity prices are going to go up,” Fishman said. “There's this external factor where inaction, I think, will become politically untenable.”

With midterms looming, time is short

Other experts are less optimistic than Fishman. Getting a bill through Congress will be challenging, in part because of the upcoming midterm elections, according to Emily Tucker, a vice president at research firm Capstone.

“We could see some movement in the spring, maybe some proposals, some conversations,” Tucker said. “But based on where things are now, it just doesn't seem like the Senate is going to be close enough to getting enough Senate Democrat agreement with where the House currently is.”

Depending how the midterm elections go, a bill could pass during a lame duck session at the end of 2026, according to Tucker. In a late-November client note, Capstone said permitting reform likely wouldn’t pass before the end of next year.

Hartman, of R Street, said the White House may not be motivated to support permitting reform.

“The White House is really confident that the permitting reforms it wants most — except for the Clean Air Act — it can pursue through executive actions,” Hartman said. “And they're confident they can do a lot of this stuff durably because of recent court decisions — in light of not just the Seven Counties NEPA case, but also Loper Bright.”

Those court decisions limited the scope of NEPA analysis and reduced the deference courts should give federal agencies.

Christina Hayes, executive director of Grid Action, an advocacy group that supports transmission development, said the bill still faces many hurdles, including government funding negotiations.

“That's going to require broader development and thinking about infrastructure and the best way to get it built,” Hayes said. “I expect to see further changes in the Senate, but it's good to have these conversations started in the House, so then hopefully it will be easier to pass when it comes back after it makes it through the Senate.”

With Democratic support remaining “elusive,” the prospects for a permitting reform deal in the Senate is challenging, according to ClearView Energy Partners.

“Democrats have consistently raised Trump Administration’s actions against renewables as problematic (as well as non-energy policies), such as the Interior Department’s July 15 memorandum requiring Secretary Burgum to personally sign off on any action that advanced solar and wind projects on federal lands,” the research firm said in a Dec. 17 client note.